Born 1962, Seoul, South Korea

In the mid-1990s, Do Ho Suh lived in a studio apartment in upper Manhattan. The fire station across the street made it hard to sleep, which got Suh longing for his peaceful childhood home. This led him to make Seoul Home (1999), a full-scale replica of the house rendered in translucent jade green silk. In theory, it could be packed in suitcases and travel with him. “It addresses issues of separation, migration, loss, and history,” he has said of the work.1 Each new exhibition location was added to the title (Seoul Home/L.A. Home/Baltimore Home . . .), to acknowledge the history it was accruing. In 2000, Suh replicated his new and presumably quieter New York apartment in fabric, again to scale. He also exhibited fabric “specimens” from the space—refrigerator, radiator, stove, sink. A fabric replica of the apartment building’s staircase , installed at London’s Tate Modern (2011), reflected Suh’s fascination with passageways. “I try to understand my life as a movement through different spaces,” he has said.2 Before vacating his New York apartment, where he lived for eighteen years, he had the interior lined with white paper and used colored pencils and pastels to rub every surface , as if to grab the memories absorbed there. Collectively Suh calls such drawings, which he’s made elsewhere, Rubbing/Loving.

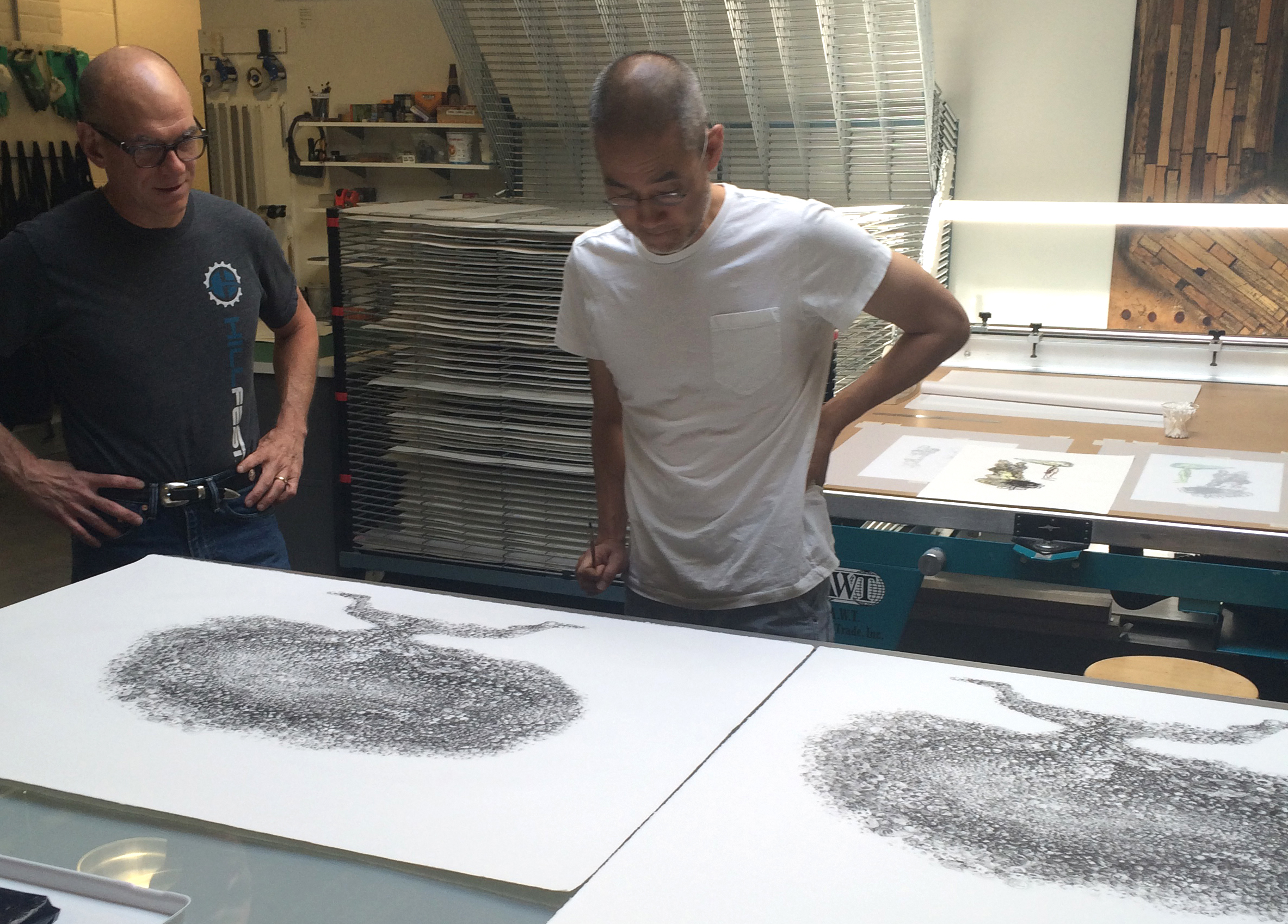

In addition to personal space, Suh is interested in interconnectedness and one’s identity as an individual and part of a group. He represented South Korea at the 2001 Venice Biennale with Floor (1997–2012)—180,000 tiny plastic figures whose upraised arms seemed to support glass flooring that visitors walk on. He also showed Some/One (2001), an armored robe made of overlapping military dog tags, a version of which is in the Minneapolis Institute of Art’s permanent collection. The relationship between one and the many could be a theme of Suh’s “karma juggler,” a recurring figure that appears in his 2015 Highpoint lithograph Karma Juggler (cat. no. 286) . Suh has often spoken about the image generally as “a man who is struggling and tangled with his karma, fate, destiny, human relationships, and the uncontrollable and unexplainable course of life.”3

Suh’s mother, Chung Min-Za, is a leader in preserving Korean heritage. His father is the eminent Korean painter Suh Se Ok. Do Ho Suh earned a BFA (1985) and MFA (1987) at Seoul National University in “Oriental painting,” a discipline he chose because it is so rarely taught. He earned a second BFA in painting (1994) at the Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, and an MFA in sculpture (1997) from the Yale University School of Art, New Haven, Connecticut. In addition to myriad group shows, including Mia’s “When Home Won’t Let You Stay: Art and Migration” (2020), Suh has had recent solo exhibitions at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (2019); Museum Voorlinden, Wassenaar, Netherlands (2019); ARoS Aarhus, Denmark (2018); Brooklyn Museum, New York (2018); Towada Art Center, Japan (2018); Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C. (2018); Bildmuseet, Umeå, Sweden (2017); NC-arte, Bogotá, Colombia (2016); Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego (2016); Singapore Tyler Print Institute (2015); Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland (2015); Contemporary Austin, Texas (2014–15); 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, Japan (2012–13); and other locations. Suh lives in London.

—Marla J. Kinney

Notes

Lisa G. Corrin and Miwon Kwon, Do Ho Suh (exh. cat.), Serpentine Gallery, London, and Seattle Art Museum and Seattle Asian Art Museum, 2002, p. 33. ↩︎

Do Ho Suh, “Rubbing/Loving,” Art21, December 9, 2016, video, 6:12, Change link to: https://art21.org/watch/extended-play/do-ho-suh-rubbing-loving-short/. ↩︎

Rochelle Steiner, “Do Ho Suh’s Karmic Journey” in Do Ho Suh Drawings, ed. Rochelle Steiner (New York: DelMonico Books/Prestel Publishing, 2014), p. 17. ↩︎