II. An Interview with Cole Rogers, Master Printer

- Dennis Michael Jon, Associate Curator, Global Contemporary Art, Minneapolis Institute of Art

Dennis Michael Jon: Cole, growing up in Birmingham, Alabama, in the 1960s and ’70s, do you recall when you first become interested in art?

Cole Rogers: I remember making and enjoying art at a very young age. My parents had studied art and always encouraged me to be creative. My mom came from a family of potters and drew beautifully. She was a draftsperson for AT&T. My dad attended the University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill on the GI Bill, and majored in literature and minored in art. He worked in advertising and newspapers back when they actually did the drawing and layout themselves.

DMJ: Did you study art in school?

CR: Definitely. I thought I wanted to be an architect and started out in engineering at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. I had taken drafting classes in high school, but due to dyslexia my math skills were incredibly poor, and I found the engineering core curriculum pretty uninteresting. I happened on an intaglio printmaking class and was hooked; I absolutely loved the process.

John Dillon, a nontraditional printmaker, became my mentor. He was interested in pop art and abstract expressionist work and was almost anti-technique. John had previously taught at Penland School of Craft in North Carolina. At his suggestion, I spent three weeks at Penland one summer making prints. I was blown away by the idea that you get up in the morning, eat breakfast, and go to the studio and work all day. There was no separation between work and art. Returning to UAB, I got very, very serious. I immediately went from “academic warning” status to the dean’s list. I really caught fire with the idea of making art my livelihood.

After earning his BFA in printmaking in 1986, Rogers left the Southeast to attend Ohio State University’s MFA program. There he met Jeff Sippel, a visiting lecturer at OSU who would go on to become education director at the Tamarind Institute’s master printer training program. Sippel encouraged Rogers to apply, which he did, despite believing it was beyond his capabilities. “I didn’t think real people went there,” he says. But Rogers was one of eight accepted applicants (five of whom already had professional experience) and moved to Albuquerque, New Mexico, in 1989. The following year, he and two of his classmates were chosen to go on to Tamarind’s master apprentice program. Rogers earned his master printer certification in 1991.

DMJ: Steve Andersen was looking for printers for Vermillion Editions, his print workshop in Minneapolis, and hired you in 1991. Was your experience with Vermillion what you expected?

CR: I was handed a couple of print projects to edition, and thirty days later Vermillion closed due to a disagreement among investors over money. So I was out of a job. Not quite what I expected!

DMJ: Was this when you started thinking about a new kind of community print studio?

CR: Not right away. I had no connections here and didn’t know my way around. Until I found work more in line with my training, I took a job at a commercial screenprinting business. It actually ended up being very interesting. We were printing circuit boards with conductive ink and all sorts of things I had never dealt with. One day they put me on the line for quality control and they very quickly found that I had a sharp eye for quality, so I was put on the more demanding projects. Then Steve Andersen got the Vermillion building and projects back, called it Akasha Studio, and I went back to work for Steve. In the evening I would pursue my own artwork.

I had this big, beautiful studio to work in but no colleagues, and that had been one of the draws to printmaking for me previously—you’d pull a print and you’d get immediate feedback. And sometimes it was you giving someone else feedback. I started looking for community studios. I joined forces with a small group of printmakers for a time, but I wanted to invite in more people, and they wanted to keep it more exclusive. I took a class at Springboard for the Arts on starting a nonprofit, just to explore. I stuck that in my back pocket and moved on.

DMJ: Did these impulses have their roots in the Tamarind program?

CR: Yes. June Wayne founded Tamarind Lithography Workshop specifically to send master printers out into the world. To me, this was the most interesting part of the program. Part of my training was to design a print studio and put together a business plan. I basically envisioned renting spaces to artists and then having a professional program that coexisted using the same presses and equipment. This was 1989, as the ’80s booming art market was crashing down and closing print shops everywhere.

DMJ: You were envisioning a multipurpose printmaking facility.

CR: Yes. I had interest but didn’t know where it was going to lead. Or how it would happen. Still, I had this feeling that we really needed something like this, like Highpoint, in the community.

DMJ: Then you accepted a position at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design. In addition to teaching, the school tasked you with rebuilding its printmaking studio. How did that experience affect your decision to found a community-based print shop?

CR: During my five years at MCAD [1995–2000], it weighed on me that, after graduating, a lot of my students didn’t have much of a next step. I counted around nineteen nearby programs besides MCAD that taught some sort of printmaking—including at Carleton, Hamline, Macalester, the University of Minnesota, the College of Visual Arts, now closed, University of Wisconsin–River Falls. None had a way for students to advance their printmaking skills after graduation. And the closest collaborative print shop was Tandem Press in Madison, Wisconsin. This all started to become problematic in my mind.

DMJ: Was there a specific moment when the idea for Highpoint surfaced?

CR: The idea had been percolating, of course. Then in 1997, the Walker Art Center had an exhibition of Frank Stella’s prints. Carla McGrath was in the Walker’s education and community-programs department. As part of the programming around the Stella show, her boss suggested she get a press to teach kids and teens about printmaking. Carla had studied printmaking at Connecticut College as an undergrad but didn’t know where to find one. Her boss said, “Well, I know Cole Rogers over at MCAD. Go meet him.” We ended up contacting Takach, a press manufacturer out of New Mexico that I knew very well, and we arranged an etching press for the Walker, with Carla teaching the classes. And I guess they thought, why not have some adult classes, too?

Carla and I taught an adult evening class together at the Walker. We were cleaning up after class, and I started talking about this crazy idea of starting a studio. And Carla said, “Will there be a place for kids there?” That was completely foreign, and nothing I’d ever envisioned. But once I went home and thought about it, it made complete sense. My interest had been in the print renaissance that had happened in the ’60s and ’70s; where was the next level of interest going to come from? The next generation needed to be exposed if we wanted printmaking to be appreciated and supported into the future.

DMJ: Did you and Carla have a shared philosophy, or mission, for this print workshop?

CR: Well, we believed in the democratic nature of prints, in making contemporary prints accessible and affordable to lots of people. As an artist, I loved the idea that my prints would exist in multiple places, could have multiple meanings to multiple people. I also wanted to instill my love for printmaking, my love of working in a studio with other people. With so many people moving toward digital media, I was concerned that fewer and fewer people would know what traditional printmaking was. When Carla brought in the idea of growing an interest in prints at an early age, the mission was also very much about education and community involvement.

This wasn’t just about commerce or people having access to presses; there was this bigger, more holistic way of looking at printmaking as an essential art form. I wanted Highpoint to be engaged in the larger conversation about art and printmaking.

DMJ: How did you develop the idea for Highpoint Center for Printmaking’s three-part structure—a professional shop, an artists’ cooperative, and an educational program?

CR: We reasoned that if you have different income streams, you’re not so dependent on one kind of funding, and eventually, hopefully, those areas feed into one another. The programs would create interest, and people who come out of those programs could possibly become professional artists. And hopefully the ones that don’t become artists but learn to appreciate traditional printmaking will support it.

DMJ: Why did you and Carla found Highpoint as a nonprofit rather than a for-profit enterprise?

CR: While we were passionate about the idea, we didn’t see Highpoint as something specifically just for us. We felt that it was something the community needed. We wanted there to be a clear mission and a board of directors so that when we stepped away, any changes made by the next leaders would have to be made according to the mission. This would ensure that the community still had opportunities to practice traditional printmaking. A new for-profit owner could just come in and say, “We’re going to start printing posters,” or “Kids are messy, let’s get rid of the kids’ programs.”

DMJ: Was the contemporary print market improving by this time?

CR: This was around 1999, and it was still pretty flat, so the idea of a diversified business model made a lot of sense.

DMJ: I imagine this venture was a big risk for you and Carla.

CR: Oh yes, and we decided early on that we were going to jump in with both feet, that we were going to give it our all. Having worked at Tamarind and Akasha, I had a pretty good idea of what was needed. Running MCAD’s print shop, I had full discretion over the budget. I knew exactly how much space you needed to run a class of twenty-some people and what they needed in that space. So an important first step of due diligence is to start a list. There’s a cutting mat. How much does a cutting mat cost? A straight-edge—how much does that cost? Razor blades, pencil sharpener. Obviously, you don’t build a functioning print studio with just a press; there are lots of small, important pieces to consider. We estimated our startup cost for the equipment and studio materials at right around $100,000.

I loved teaching at MCAD, and Carla loved working at the Walker. Again, neither of us were seeing this as a move just to benefit ourselves. In fact, we both took huge wage cuts and losses to do it and had to pool our money to purchase the equipment, but after two years of research and planning, it seemed highly possible that this could be successful.

Sticking to Traditional Techniques

DMJ: How did you decide to establish Highpoint Editions as a separate publishing entity?

CR: We had different work coming out of the artists’ cooperative, the classroom, and the professional shop. When we were exhibiting at print fairs and doing marketing, we needed to differentiate the work by the artists we selected, worked with, produced prints with. Our hybrid shop model was novel to serious collectors and the different kind of work coming out of HP could be confusing to them. So, we created a separate identity, or brand, called Highpoint Editions.

DMJ: Artists working with Highpoint Editions are limited to the techniques of relief, intaglio, lithography, screenprinting, and monotype. Was this always your intention?

CR: Yes, definitely. But I wouldn’t quite say “limited”—many shops specialize in a single print medium like Tamarind Institute or Crown Point Press.

DMJ: Given the prevalence of digital printmaking, why does Highpoint remain committed to these traditional techniques?

CR: In the ’90’s I was really enamored with the potential of integrating digital technology with printmaking. Digital can produce quicker results than, say, etching and aquatint, where you’re applying grounds that need to dry, etching plates for long periods, and physically scraping and burnishing to make corrections. But while digital media is quick, it is often very limited. Your paper choices are limited, your scale can be limited. When teaching, I tried to introduce some of the qualities of printmaking into the digital aspect, but I found that creativity doesn’t flow very readily between the two forms.

It seemed like digital is where everyone was going. And just about every program was cutting back on the traditional methods. The same space dedicated solely to a single class of ten lithography students could be turned into a digital lab for twenty students in several classes per day—adding a big incentive to go digital. There needed to be a place dedicated to the longevity of traditional printmaking media for future generations.

I don’t feel that traditional printmaking is better than digital, and Highpoint does have ways to utilize digital capabilities. But with digital so widely available, why would we want to replicate that? I just have never found traditional printmaking lacking. There’s very little it can’t do, and it can do a lot of things that digital can’t. The direct, unmediated experience of traditional printmaking really lends itself so well to creative possibilities.

Working with Professional Artists

DMJ: How do you identify artists you’d like to work with at Highpoint?

CR: Our list is very long—and growing longer. There are more interesting artists than we could ever work with. The challenging part is getting them in. It took Willie Cole at least eight years to find a place in his schedule for us. Most of the artists we’re interested in have families, an active practice, and a studio to run. That all gets interrupted if they travel to Minneapolis, so they are making a commitment.

DMJ: What factors go into your decision to invite an artist to make prints?

CR: I hate to go immediately to money, but probably first and foremost we need to make work that will help support our future publication projects and public programs. We would soon run out of funds if we produced work we couldn’t market, because Highpoint is supported to a large degree through print sales.

We are approached constantly by people who want us to make a print with them, thinking they’re going to make money by association. If it were that easy, we would be making wheelbarrows of cash. And there would be a lot more shops like us. It’s got to be the right print for the right moment, the right audience, and building a platform to get it in front of that audience. The art business is hard; it is really, really hard.

DMJ: So, an artist’s reputation and market potential are important considerations.

CR: Very much so. If an artist is performing well, has gallery representation, and has a pretty solid market, that’s incredibly helpful. It’s not always a guarantee. If we put $20,000 to $30,000 into a project and get no returns to pay for the staff, materials, and overhead, we would close very quickly. Once we identify artists, we follow them for a while, watch how their career is going. There are artists that we’re looking at now who may be at the right place in a few years. We also like to bring in artists whose work is becoming less affordable, because producing multiples makes the work more accessible. We also look at whether an artist has a huge number of prints out there already. If so, why make more? Early on, I liked that our booth at the Print Fair in New York had work by artists that people hadn’t seen prints by before, unlike booths that seem to be chasing the same artists.

DMJ: How do you approach artists who you might wish to invite to Highpoint?

CR: It usually starts with a visit to the artist’s studio. You can tell a lot by the way the materials are laid out, the way the materials are used, the organization of the studio. You can tell very quickly what the artist’s art-making process is. That’s pretty much your first clue as to how this person would deal with printmaking. Printmaking can be rather restrictive; it might not be right for someone who is resistant to process, who is apt to do things spontaneously, who chafes at having to wait during the various pauses that printmaking entails.

DMJ: As Highpoint Editions has become better known, has it become easier to attract top talent?

CR: To some degree. It’s always going to be difficult being in the Midwest compared to, say, San Francisco or New York, where you can ask someone to jump on the subway and come for an afternoon to try something. There is a reason lots of artists and print shops are located there—access. Luckily, we are also at a place now where we can both attract those artists as well as introduce artists who are less well known.

DMJ: Do you consider geographic diversity?

CR: That’s always a consideration. When we were trying to get off the ground, we went to artists within easy reach, artists who already had a network and market we could tap into. Local artists are important because they often have more flexibility to come in and work than national and international artists. I think it’s very important for the local community to feel appreciated. It’s all too common for locally based artists to feel that they’re being overlooked, that all the talent is coming from outside, so we try to keep a balanced program.

DMJ: What has been Highpoint Editions’ role in supporting women artists, artists of color, LGBTQ+ artists, and others in its publishing activities?

CR: When we first started Highpoint, I actively tried to enlist a diverse roster of artists. We didn’t yet have a reputation, which may have been an issue. I asked Willie Cole to make prints at Highpoint in our first year but was rebuffed. I made a studio visit with Glenn Ligon early on. I invited Kara Walker and other artists. It would have been very difficult for us as a new studio to bring an unknown artist of color to Highpoint and produce the work and develop a market for them at the same time. But a look at the list of artists published by Highpoint Editions shows we have steadily and very intentionally built a strong diverse roster of artists over the years as we have become known and have built out our publications platform.

In 2020, Njideka Akunyili and Delita Martin (cat. nos. 184–90) were here working in January. We were working with Rico Gatson on coming back into the studio. I was talking to Julie Buffalohead about returning in the fall. (She wasn’t able to until the summer of 2021.) We also were working with Jim Hodges (cat. no. 163–66) . We were planning a project with Julie Mehretu . We had just finished work with Dyani White Hawk (cat. nos. 296–98) . All of those artists fall into at least one of the groups you are asking about. And we are very proud of it. When George Floyd was murdered, it was a wake-up call to a lot of white America. Growing up in Birmingham, Alabama, I thought I recognized racism when I saw it. I believed a lot of what I was told as far as everybody having a fair shot. I think that our society has always given us a story that leaves out a lot of other stories, whether in education, media, movies, etc. I became increasingly aware of this within the art world as well and we are working to address it.

DMJ: What happens after an artist arrives at Highpoint?

CR: First I present two or three processes to see what they’re most comfortable with. I try to leave things as open as possible. I really want the artist’s involvement with the materials to be evident in the final work. My attitude is that initially it’s not just about making art; it’s about getting involved with exploring the process’s potential. Over the years, I’ve noticed that a lot of studios seem to have a certain look. Or there’s a shop style, which develops when a shop dictates a particular way it wants people to do things. That’s something I’ve wanted to avoid. I want a range of voices and a range of ideas from a diverse pool of artists to make up HPE publications.

DMJ: What’s your creative approach to collaborating with professional artists?

CR: If I have one, it grows out of my own experience as an artist. When I was teaching, I only had about twenty hours a week in the studio to make my own art. It all became very precious. I stopped taking as many chances because I knew that I needed a certain number of pieces and sometimes I would finish them in ways that I understood, and they would be good enough. I started making things that were very safe. But I was no longer taking risks and making discoveries.

I’m a technician who’s there as kind of a safety net for the artist, not running the show. I’m there to help and collaborate, not direct. My philosophy for the artist is, get in there and experiment, make messes, and let’s go places you didn’t know when you walked into the studio this morning. If something fails, at least the artists know they’ve got somebody who’s on their side and willing to take risks on their behalf.

DMJ: In your role as master printer and technical guide, how much do you shape the final product?

CR: No more than I have to. It’s important not to bring your own aesthetic or ideas of what is good or bad. I experienced this at Tamarind with Eric Avery. I handed him a tusche mixture and told him to stir it and not shake it because shaking would create bubbles. Well, he shook it up and painted with it and it made the most incredible patterns—bubbles on the surface. That happens all the time. That’s part of the collaborator’s dance: how far out on a limb do you let artists get, and it is not always comfortable!

Some artists want a lot of guidance; others want you to be the technician and they want to tell you what to do. Sometimes an artist will want something that is virtually unreasonable from a technical point of view. Usually, I’ll discuss the pros and cons of the approach and leave it up to them. Sometimes they’re right and I’m wrong and the thing that seemed unreasonable gives us something great. The last thing you want is to say no all the time.

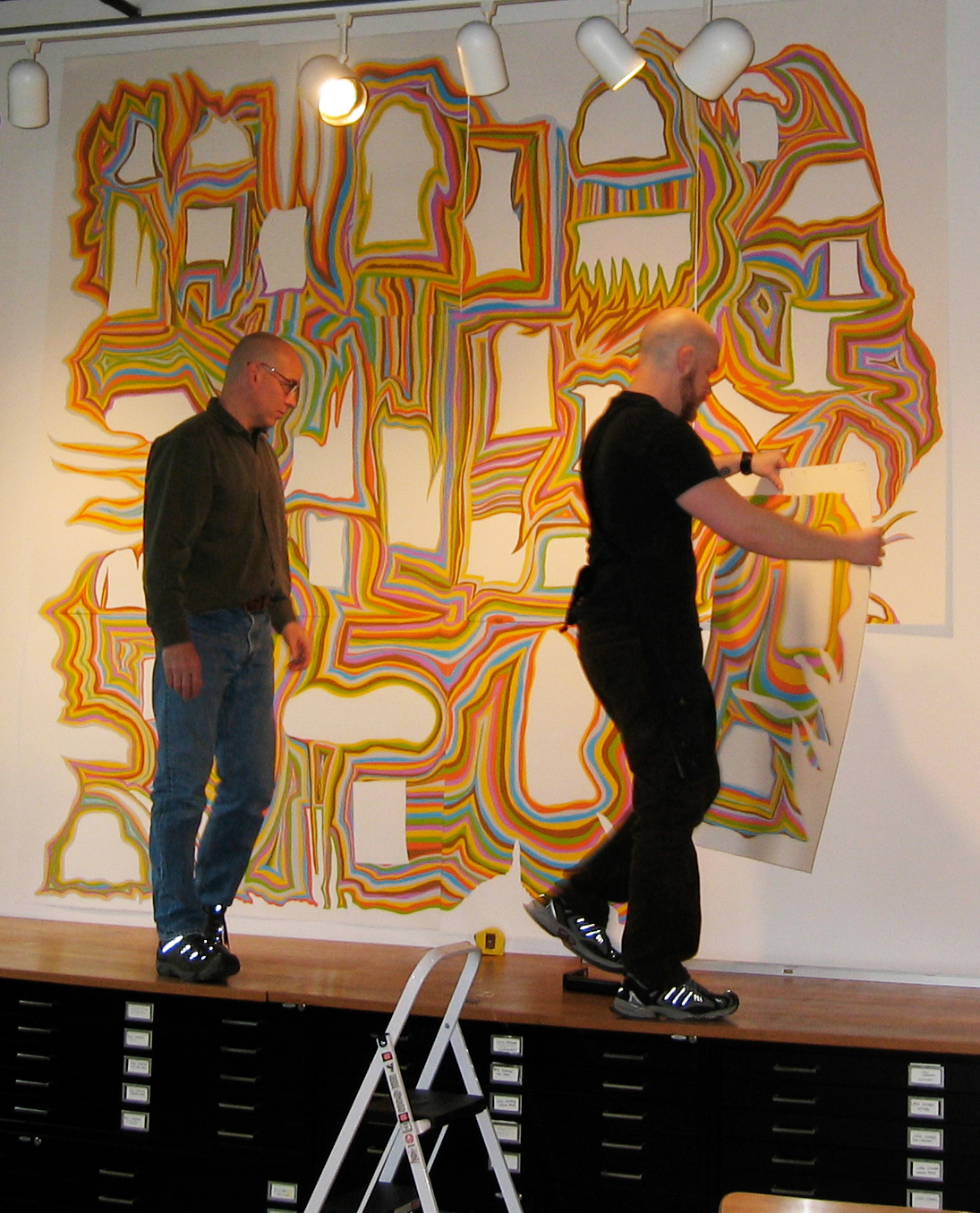

Santiago Cucullu proposed a 10 x 10-foot panel (cat. no. 90) consisting of twelve prints using screenprinting and lithography. This really worried me—I just didn’t see how we were going to place enough of these panels to justify the project costs. We produced the panels, but I also talked Santiago into issuing some images from them as a series of small prints. But my instincts were incorrect—the large portfolio sold out and the small prints didn’t do so well at all.

DMJ: You once said you like working with artists with little or no experience in printmaking. Why is that?

CR: People who have made prints before have all these rules in their head. They might think you should be mixing ink a certain way or handling a roller a certain way. That can be a problem. And they may be basing [their Highpoint project] on past knowledge, not coming in looking for something new. Artists with less experience are able to reimagine the materials they’re handed. When I was teaching at Ohio State, a favorite assignment was to tell students to go out and find sticks. They’d bring back these long, weird things, then you’d have them put paper and an inkwell on the floor and draw with the stick. It was hard to do; they would get really angry. They wanted their number two pencils, which they’d grown up using. But there was a certain intensity to the stick drawings that had to do with resistance and trying to get something to work that their comfortable number two pencil drawings didn’t have.

DMJ: Along those lines, why would someone who’s primarily a painter or sculptor choose to make prints?

CR: Exploring how to get something done in one medium can stretch artists and give them a fuller vocabulary of creative tools, which can then be transferred to other media. It’s like having another instrument in an orchestra.

DMJ: At what point did you feel that Highpoint Editions was a success?

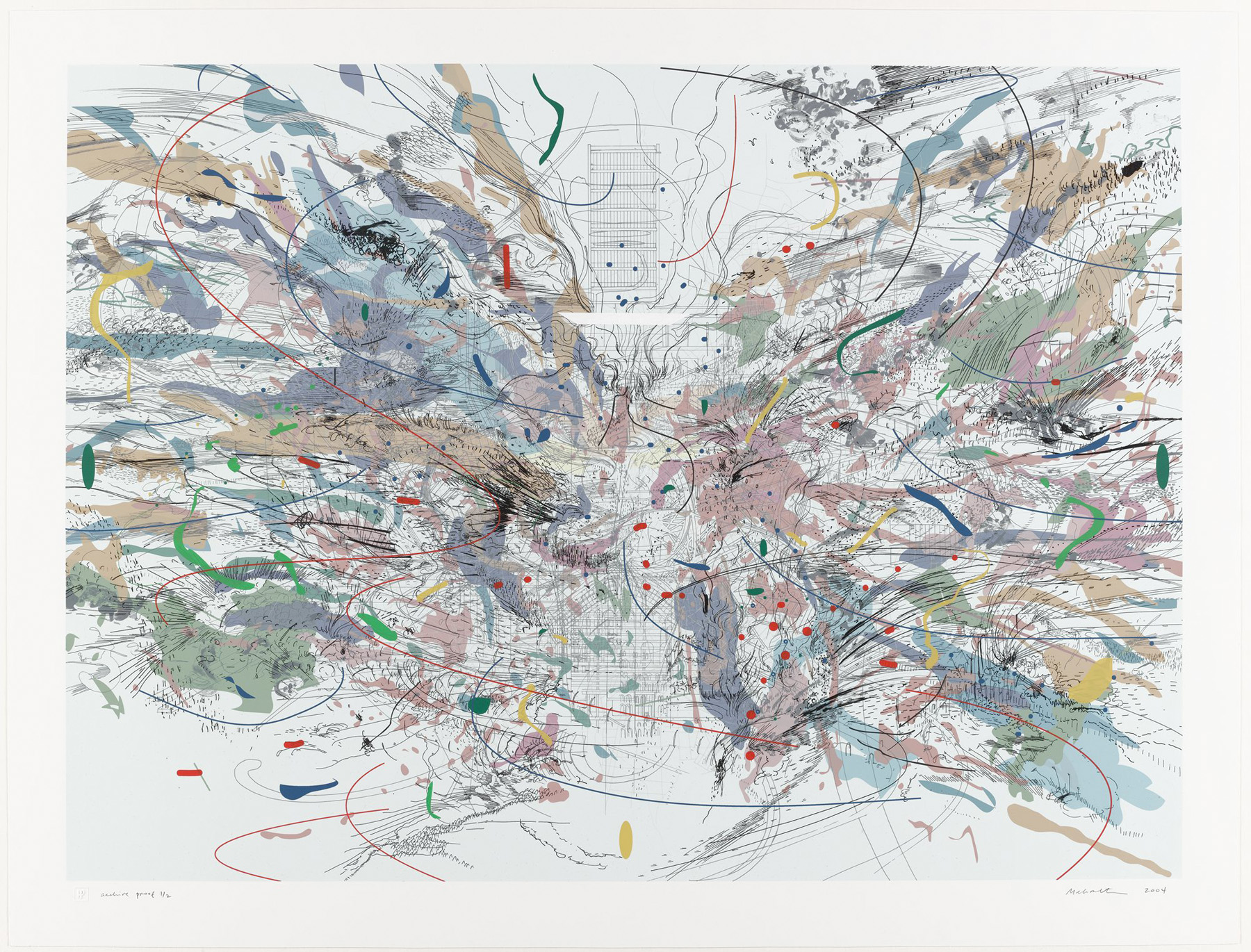

CR: It has to be Julie Mehretu’s print Entropia (review) (cat. no. 191) which is already becoming a classic. Back then, in 2004, she had only made a couple of professional prints, and these were basically contracted editions with set budgets, done to benefit institutions.

When she arrived at Highpoint, Julie said, “How many colors can I do?” I said, “Well, we’ve got skin in the game. As far as I’m concerned, you can do as many colors as you want. I want you to love this print. I want this to be something that you’re really proud of.” And I added, “If you’re proud of it, then I know it’ll be great.” We ended up using thirty-two colors. It sold out quickly and was a huge critical and commercial success.

DMJ: Were there any print projects that you found especially challenging?

CR: One was Mungo Thomson’s “Pocket Universe” series (cat. nos. 293–94) . That project started as coins that were inked and printed in the press. The result was kind of ho-hum. We looked around, found some embossing foil, and got beautiful impressions of the coins. But we had to battle dust like crazy while making them. If you look at a polished Donald Judd sculpture, you notice any speck. Likewise, Mungo’s pieces were highly polished and any speck of dust that got under the foil would create an irreparable pimple on the surface. Our team worked for quite a while getting these done, then we put them in boxes. Three months later we discovered they were corroding: metal dust particles from the coins had embedded themselves in the back of the foil and started eating through to the front by a process called galvanic corrosion. We had to remake them all—it was just one of those unexpected challenges that make you crazy.

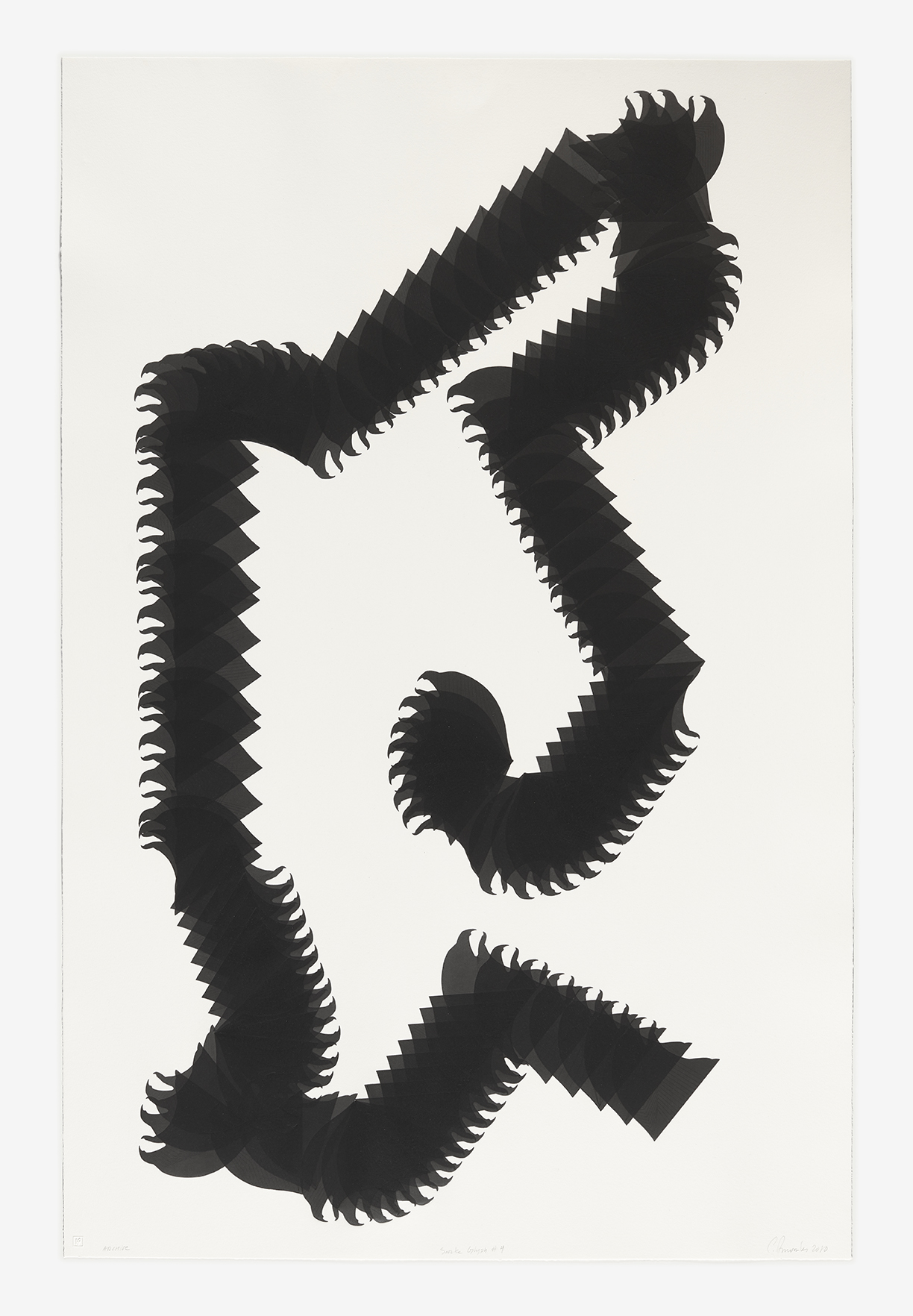

Carlos Amorales’s “Snake Glyph” series (cat. nos. 15–19) had something like up to 176 little plates for each print. For each image, the plates were inked and rearranged seventeen times, so the sheet had to go through the press seventeen times as well. Since the process was intaglio based, the paper had to be dampened before printing, allowed to dry after printing each layer, and dampened again before printing the next layer the next day. Each time, the 3 x 6-foot piece of paper had to shrink and expand at the exact same rate and be laid very precisely before printing over a course of seventeen days, and a mistake on day seventeen would destroy the other sixteen days of work. You have to pay attention and be precise.

DMJ: In our conversations, you’ve mentioned the technical challenges of Jim Hodges’s “Seasons” suite (cat. nos. 159–62) . What made it so demanding?

CR: Jim is a very intuitive worker. He tends to tear things up, tape them back together, draw on them, cut them, or destroy them, all in search of the essence of the print. It’s going to reveal itself to him, but he doesn’t really know how he’s going to get there. Since his process is nonlinear, we basically had to reverse engineer everything once he arrived at his idea. But while Jim is demanding, he’s not unreasonable. For example, for Bringing in the Ghosts (cat. no. 162) , he wanted to produce a relief print from sixty-four blocks arranged like a jigsaw puzzle. I said this would be ecologically a mess because we’d have to prepare sixty-four different slabs of ink and ink sixty-four brayers and maybe get two or three impressions printed a day, then clean up all that ink and all those brayers, which would mean a lot of solvents, a lot of rags, a lot of wasted ink, then start over the next day. I said we could convey the same language lithographically. So we transferred his woodblocks to lithographic plates.

DMJ: For Delita Martin’s “Keepsakes” series (cat. nos. 184–90) , you used actual christening dresses to produce collagraphic printing plates. How did this come about?

CR: Delita came in with antique christening dresses. If you ink and print the actual dress, you’d end up with only one print for each dress. We wondered whether there was some way to make multiples since she had a limited number of dresses and they are hard to find. First, we took apart a christening dress and laid the front directly on a photo-litho plate and exposed it. The threads were able to transfer, and it printed great. But it was quite flat. I proposed making a collagraph plate of the image. We coated a litho plate with gel medium and had Delita arrange it the way she wanted, then tried inking it. It was beautiful. This version read with dimensionality, both visually and physically—the folds had this incredible dimension.

This experience demonstrates what I love best about traditional methods: they are so directly about surface. Information being transferred from one surface onto another one. That is the essence of what a print is. There’s no need for a lot of gadgetry or complicated processing. There’s just simple elegance, and it’s so poetic.

Looking Ahead

DMJ: Though Highpoint Center for Printmaking was founded on the idea of local community engagement, do you see Highpoint Editions participating in the larger, even global, community of print workshops?

CR: Yes. That’s one reason we didn’t call it Minnesota this or the North Star that. We wanted a name that would transcend the local. And hopefully we would be engaged in the larger conversation of art and printmaking.

DMJ: Highpoint celebrates its twentieth year of operation in 2021. What are your thoughts about Highpoint’s future? Do you think it will endure as a community-based printmaking center?

CR: I certainly hope that we always have a prominent place in the community and serve it well. We caught a lot of guff early on from other print dealers and publishers who didn’t understand why we should be eligible for grants, and why we were started as a nonprofit. They thought that it was a tax dodge or that we had some unfair advantage based on their opinions surrounding university-affiliated studios. And in some ways, it would’ve been easier to go a different route. But the nonprofit structure helps ensure that any changes must adhere to the mission statement and can’t be done on a whim. From the very start we wanted Highpoint to be as permanent as anything can be. I mean, will Highpoint be here in a hundred years? Probably not. But I think we’ve done everything possible to point it in that direction. Our hope is that as long as there’s a need, Highpoint will be there to fill it.

DMJ: What does it mean for the Minneapolis Institute of Art to acquire the twenty-year archive of Highpoint Editions for its collection?

CR: Having Highpoint’s prints in a setting where the public has permanent access was always our hope and dream. It’s great to have our prints in other public collections—and in private hands, too—but a museum setting is where Highpoint artists can be put into a historical context, a lineage; you have another way to understand the work we and they are doing. We also wanted the work to be seen and be a living resource. A lot of archives exist, but they exist in flat files and are rarely seen. With Mia’s dedication to collecting prints, to growing their collection of contemporary art, to having an active print study room, specialist curators and staff, and dedicated print galleries, as well as no admission charge for the public, I think Mia is the perfect home for the Highpoint archive. It is the kind of accessibility we could never offer and is very rare today.

DMJ: Looking at Highpoint Editions over the past twenty years, what stands out as your proudest achievement?

CR: It’s funny, because every now and then I’ll run across someone in a different city, and they’ll know about us. They’ll say, “We’ve heard great things.” It just feels so wonderful, like we’ve created this thing that outlives us in many ways. I walk through the studio and see all these people using it, and all these people at our art openings, and all the employees and interns we’ve worked with over the years. I think about introducing artists at art fairs, having collectors and curators come back to our booth to see what we’ve published this year. You can’t beat that feeling. The connective tissue is that it’s all about people and relationships. It’s been an incredibly difficult endeavor at times, but a very rewarding journey.

DMJ: Thanks so much, Cole.

CR: My pleasure.