I. Building on Tradition: The Story of Highpoint Editions, 2001–2021

- Dennis Michael Jon, Associate Curator, Global Contemporary Art, Minneapolis Institute of Art

In the spring of 2001, Highpoint Center for Printmaking welcomed its first visitors to its newly opened studio and gallery in a modest street-level storefront in the Lyn-Lake commercial district of South Minneapolis.1 The brainchild of cofounders Carla McGrath and Cole Rogers, the center was among only a small number of independent nonprofit printmaking centers in the country and the first of its kind in Minnesota. Highpoint’s mission was straightforward: to support and promote an appreciation and understanding of the printmaking arts. It would achieve this through diverse community-based educational programs, a co-operative printmaking studio (artists’ co-op), and a professional shop—Highpoint Editions—that publishes fine art prints made by invited visiting artists working in collaboration with Rogers and workshop staff.

Highpoint Editions modeled itself on the pioneering print studios that began in the late 1950s and 1960s, among them Universal Limited Art Editions (ULAE) , Tamarind Lithography Workshop , Crown Point Press , and Gemini G.E.L. . Their founders were visionaries who hoped to revitalize fine art printmaking in the United States by inviting leading painters and sculptors to make original prints. The pivotal idea was collaboration: the artist contributes the concept and imagery; the master printer provides technical expertise, printmaking materials and equipment, and a place to work.2 It’s a production model that dates back centuries, when labor was divided among artists, designers, printers, and skilled specialists such as block cutters, colorists, or interpretive engravers. The degree of collaboration has varied since, from contract printing, which requires little or no contact between artist and printer, to a cooperative model, in which an artist also serves as printer with only minor technical assistance, to a fully collaborative model, in which artist and master printer work as a team in a joint creative endeavor.3

The artist–master printer collaboration as we know it today—which commonly entails publishing and marketing prints—was the innovation of Tatyana Grosman, who established the now legendary Universal Limited Art Editions (ULAE) in 1957 in a gardener’s cottage on Long Island, near New York City.4 Initially, she planned to print and publish illustrated artists’ books. On the advice of print expert William S. Lieberman, a longtime curator at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, however, she began producing lithographs by some of the leading vanguard painters and sculptors of the postwar period, including Larry Rivers, Jasper Johns, Grace Hartigan, Robert Rauschenberg, Helen Frankenthaler, Robert Motherwell, Lee Bontecou, and Jim Dine. Many of the early ULAE artists had never made a print, but each brought innovative ideas to the once solitary and decidedly old-fashioned medium of printmaking. Together, they helped make the medium integral to contemporary art.

The success of ULAE prompted other collaborative print workshops to emerge.5 In 1960, American artist June Wayne founded Tamarind in Los Angeles as a printer-publisher of original lithographs and a training ground for master printers.6 Up the coast, Kathan Brown opened Crown Point Press in Oakland, California, in 1962. Now located in San Francisco, the workshop specializes in intaglio printmaking. In 1966, Kenneth Tyler established Gemini G.E.L. in Los Angeles, which became known for innovative printmaking techniques that included three-dimensional multiples. In New York, Eleanor Magid founded the Lower East Side Printshop in 1968 as a nonprofit, open-access art and community center. The same year, Adolf Rischner established Styria Studio in Glendale, California, a print workshop and publisher that later relocated to the SoHo neighborhood of New York City (now closed). In the years that followed, collaborative printmaking ventures have sprung up in such varied locales as Tampa, Florida (USF Graphicstudio)

; Chicago and Albuquerque, New Mexico (Landfall Press)

; Boulder, Colorado (Shark’s Ink)

; Mount Kisco, New York (Tyler Graphics); Madison, Wisconsin (Tandem Press)

; and St. Louis, Missouri (Wildwood Press)

, among many others.

A Shared Vision

Like many arts organizations, Highpoint Center for Printmaking was years in planning before McGrath and Rogers made the inherently risky decision to open a nonprofit arts center in 2001—a decision further complicated by the economic recession that began in March of that year and lasted until November.

Serendipity was a decisive factor in Highpoint’s founding and ultimate design, specifically a fateful meeting of its two founders in August 1997 when they collaborated on a public printmaking demonstration sponsored by the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. At the time both McGrath and Rogers were active in the local arts community, McGrath as a tour guide and art lab coordinator at the Walker, and Rogers as an instructor and printmaking studio manager at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design (MCAD). Though the two had known each other informally, it was this occasion and their subsequent conversations that sparked the idea of joining forces to establish a community-based printmaking center. Though Rogers’s training and background in printmaking were formidable, and McGrath’s legal background,7 writing skills, and teaching experience would be essential to Highpoint’s eventual success, neither McGrath nor Rogers had significant business experience. Both, however, were careful and deliberate planners with strong visual arts backgrounds. They also understood the critical importance of seeking outside expertise and collaborating with the local arts community to develop their business plan.8

McGrath was born and raised in Ashville, Ohio, just east of Cleveland. Her parents believed deeply in supporting the performing and visual arts, even helping to found an arts center in Ashville. McGrath took several studio art classes while earning a bachelor’s degree in English at Connecticut College in New London, in 1982. Soon after, she moved to Minnesota to attend Hamline University School of Law (now Mitchell Hamline School of Law), in St. Paul, and received a JD in 1986. Meanwhile, she continued to pursue art, taking printmaking classes at the California College of Arts and Crafts (now California College of the Arts) and the University of Colorado, Boulder. The decision to make teaching part of Highpoint’s mission grew out of McGrath’s experience in arts education and her passion for offering art-making experiences to children and teenagers, especially those whose lives rarely included art and creative opportunities.

Rogers, a native of Birmingham, Alabama, was an only child whose family stressed personal creativity. Although he entered the University of Alabama at Birmingham with thoughts of becoming an architect, his plans shifted after an introductory intaglio printmaking class with John Dillon (1935–2019). The class, and Dillon’s offbeat enthusiasm, sparked Rogers’s lifelong fascination with the technical challenges and creative possibilities of printmaking. Dillon also instilled in Rogers important lessons of focus and discipline. After graduating with a BFA in 1986, Rogers entered the prestigious MFA studio art program at Ohio State University in Columbus, where he met visiting artist and lecturer Jeff Sippel, another important mentor. It was Sippel who urged Rogers to apply to the Tamarind Institute, then as now the premier training ground for lithographic printers in the United States.9 In the late 1980s, Rogers advanced to Tamarind’s heralded master printer apprentice program. One of the program’s guiding principles is that graduating master printers are urged to establish independent print workshops in their home states and countries.

This ideal was never far from Rogers’s mind as he formed his vision for Highpoint’s publishing arm, Highpoint Editions. The workshop Rogers visualized would create unique and limited-edition prints using one or more traditional printmaking techniques: relief, intaglio, lithography, screenprinting, and monotyping. And as a traditionalist, Rogers excluded digital (computer-assisted) printmaking processes, though he would integrate photographic imagery when part of an artist’s creative process.10 As soon as the center was a reality, he faced the immediate challenge of developing a stable of noteworthy professional artists to collaborate with. That his new press was located in the Upper Midwest, a northern climate with long winters, far from the country’s major art centers, made attracting leading national and international artists a challenge. He knew it typically took years of successful prints for a new workshop to build a national reputation. Therefore, Rogers took the initial approach of seeking out prominent artists who lived or worked in the Minneapolis–St. Paul metropolitan area or had other ties to the state. In curating his pool of collaborating artists, Rogers had certain general requirements. He wanted artists with varied backgrounds and interests. He wanted a balance of local, national, and international figures who would bring diverse thoughts and expressions to the press. Also essential was an openness to experimentation, discovery, and adventure. In addition, he wanted to avoid establishing a single aesthetic or “house style” for Highpoint’s publications, and this, too, became part of his calculation. And importantly, in keeping with Highpoint’s mission-based commitment to access and inclusion, Rogers was determined that his recruiting efforts encompass diversity in gender, race, ethnicity, culture, and sexual orientation. All of these desiderata became easier to realize as Highpoint gained in national prominence.

Unlike at some print workshops, Highpoint’s fortunes are not tied entirely to sales of prints. McGrath describes the center’s organizing principle as a “three-legged stool,” a metaphor for operational stability that lessens dependence on any single source of revenue by providing multiple income streams for the enterprise.11 This multifaceted organizational structure was modeled in part on the highly successful nonprofit arts centers already operating in Minneapolis, most notably the Northern Clay Center

and the Minnesota Center for Book Arts

.12 Founded in 1990 and 1983, respectively, these specialist arts organizations operated as community-based businesses whose media-dedicated ventures were designed to assure long-term economic stability. Highpoint’s nonprofit status was also critical to maintaining its financial security, allowing it to make public fundraising appeals as a charitable organization and qualifying the organization for myriad arts and educational grants offered by local and national foundations and government agencies.13 To Highpoint’s advantage, Minnesota enjoys a strong tradition of public funding for the arts. Indeed, Minnesota leads the nation by a wide margin in per capita legislative appropriations to state arts organizations.14 Minneapolis–St. Paul itself has an enviable legacy of private, corporate, and foundation support for the arts.

First Steps

For Highpoint Editions’ first workshop collaboration, Rogers tapped Minneapolis-based painter and printmaker David Rathman . Inviting Rathman was a logical choice, as he was well regarded locally and nationally and was experienced in multiple printmaking techniques. In addition, his art was reliably in demand. Rathman and Rogers were also well acquainted with each other’s practices. In the 1980s and early 1990s, Rathman made several editioned prints and artist’s books at the Minneapolis-based print workshop Vermillion Editions Limited, now closed.15 As a result, he was intimately familiar with the procedures and deliberative pace of workshop practices. Rathman began his collaboration with Rogers in September 2001, and by May 2002 he had completed plates for six sepia-toned intaglio prints featuring wry scenes of cowboys he had adapted from classic western films, a subject he had first rendered as ink-wash drawings. Accompanied by quizzical passages of text, the “cowboy” prints were part of Rathman’s recurring efforts to use images of physical conflict to question societal expectations of modern American masculinity.16 Published later that year, “Five New Etchings” (cat. nos. 248–52) , along with a sixth print editioned separately (cat. no. 253) , were an immediate success. Rathman would return to Highpoint Editions in 2009, 2011, and 2017 to produce various monotypes and editioned prints on subjects ranging from ice hockey (cat. nos. 258–67) to demolition derbies (cat. nos. 255–57) .

In February 2002, Rogers invited midcareer artist Linda Schwarz to Highpoint. A native of Germany, Schwarz was a technically sophisticated printmaker who had studied art and art history at the University of Minnesota in the early 1990s. She was also known to curators at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, who had earlier acquired examples of her self-published print work.17 Like Rathman, Schwarz possessed a formidable knowledge of printmaking techniques and processes. She bases her work on the appropriation and alteration of existing imagery, a process that frequently involves layered images and hand-painted additions in ink, acrylic, and varnish. She derives much of her material from German history, obscure sources of art, literature, poetry, and music, and even pop culture.18 Schwarz refers to her subject matter as “lost language—forgotten knowledge.” For her Highpoint prints (cat. nos. 269–73) , which explore the language of hand gestures, she refashioned images of sculpted hands by the German late Gothic and early Renaissance woodcarver Tilman Riemenschneider (c. 1460–1531). In keeping with her penchant for material experimentation, each print edition is variable.

With two Highpoint projects realized, Rogers resumed his focus on accomplished local artists.19 Next, he invited the St. Paul drawing specialist and art educator Mary Esch , whose practice centered on portraiture and pictorial narratives adapted from fairy tales and other literary sources.20 At Highpoint, she decided to refashion Leo Tolstoy’s short story “The Three Questions” (1885) into a series of twelve soft-ground line etchings (cat. nos. 127–40) . Substituting Tolstoy’s king for a queen, she unveiled a life-affirming journey of discovery and redemption. In Esch’s portfolio, the queen’s travels end with a poignant reminder to alleviate suffering immediately for the person who needs it most.

In early 2003, Rogers invited Minneapolis-based painter and printmaker Todd Norsten

to Highpoint. An accomplished midcareer artist and former printer at Vermillion Editions, Norsten was enjoying increased national recognition after recent exhibitions in Chicago, San Francisco, and Milwaukee, as well as at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. For his Highpoint project, the first of several collaborations he would undertake with Rogers (he returned in 2009–11 and 2016), Norsten created delicate color intaglio prints featuring abstract and semiabstract imagery derived from natural forms and manufactured objects (cat. nos. 223–31)

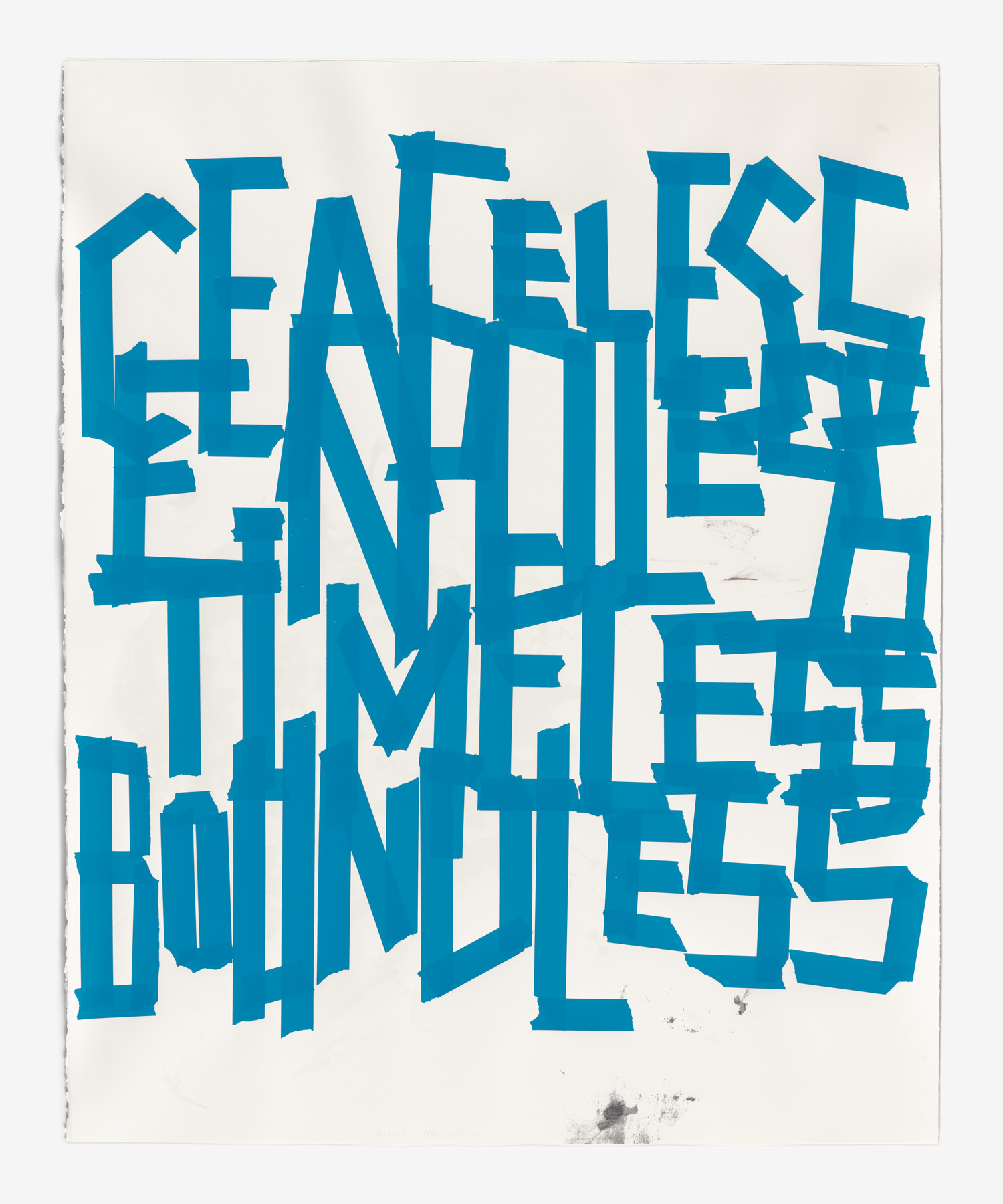

. Though initial sales of Esch’s portfolio and Norsten’s intaglios were modest, their release affirmed Rogers’s commitment to Highpoint’s artist-driven publishing program. For his later Highpoint projects, Norsten adopted a dramatically different formal and conceptual approach that gave rise to various unique and editioned text-based prints in lithography, screenprinting, and monoprinting.21 Among them were several trompe l’oeil (fool the eye) compositions featuring stacked words that at first appear to have been composed from torn lengths of blue or beige masking tape, including Endless, Ceaseless, Boundless Joy, 2009 (cat. no. 232)

; Ceaseless, Endless, Timeless, Boundless, 2010 (cat. no. 234)

; and Wayland, 2013 (cat. no. 237)

. Part jest, part sardonic commentary, Norsten’s “word drawings” recall the illusionistic ribbon-word drawings of Ed Ruscha, who in the late 1960s and early 1970s used gunpowder and pastel to depict solitary words seemingly composed of lengths of paper ribbon.22 Rendering this type of picture as a printed image—including the tactile thickness and texture of masking tape—required dismantling the image into fragmentary components that were then printed separately in perfect alignment—a demanding and precise undertaking. Rogers was up to the challenge. He noted the project’s technical achievement: “Norsten’s masking tape prints were a standout of marrying image and technique, especially the very first masking tape print. That was a real stunner, how all of a sudden you see the physicality achieved by the screenprinting, how we created a trompe l’oeil of masking tape.”23

Growing Prestige

With the early publications by Rathman, Schwarz, Esch, and Norsten, Highpoint Editions had dipped its toe into the highly competitive contemporary print market, an ambitious effort for a new and largely unknown press. Rogers and McGrath made equally bold decisions about how their prints would be marketed. Unlike publishers who routinely offer deep discounts to galleries and private dealers to sell their prints, Highpoint chose to market its prints directly to collectors and curators, without the aid of dealer-agents.24 This tactic supported the workshop’s desire to maximize income for visiting artists and place work in the permanent collections of public museums. Aside from its copublishing efforts, Highpoint absorbed the bulk of production costs rather than deduct these from the artists’ portion of print sales. Most publishers routinely deduct labor, materials, overhead, travel, or other project costs before splitting sales proceeds with the artist. But in the view of Highpoint’s founders, this practice does not sufficiently credit or acknowledge the artist’s considerable contributions.25 This payment structure was unusual among print publishers but aligned with Highpoint’s intention to share any profits with visiting artists more equitably.

Early on, Highpoint announced its new publications on its website, in national art journals and the center’s self-published newsletter, and on the walls of its exhibition galleries.26 In every case, Rogers and McGrath were careful to communicate the Highpoint Editions brand as a national fine art printer and publisher. Rogers also knew that market success was correlated with workshop reputation, and that Highpoint’s reputation hinged on attracting top national talent. Because Highpoint Editions was founded as a subsidiary of the nonprofit Highpoint Center for Printmaking, income from print sales would help support the center’s operations and programs, while the center’s unrestricted income would offset a portion of the costs of producing and marketing workshop prints. Thus, for Highpoint Editions to be successful in the long term, the entire organization had to be financially stable.

In confronting the many challenges facing their fledgling organization, founders Rogers and McGrath understood the importance of seeking expertise from Highpoint’s stakeholders and the wider community. Highpoint Center for Printmaking’s status as a registered nonprofit corporation required establishing a board of directors, the governing body of the organization’s mission, strategy, and goals.27 Highpoint’s leadership had always envisioned a “working board,” whose members would contribute expertise from their respective professions or areas of interest in addition to financial support. Rogers and McGrath recruited members from the fields of law, finance, education, and business but also sought those with ties to the local arts community,28 including working artists, gallery directors, and curators from local art museums.29 To further leverage board expertise, Highpoint formed a curatorial committee of members with knowledge of contemporary art and the contemporary print market who could assist Rogers in identifying and recruiting artists to collaborate at Highpoint Editions. Indeed, the museum curators on the committee routinely introduced their institution’s visiting artists to Rogers with the prospect of future collaborations in mind.

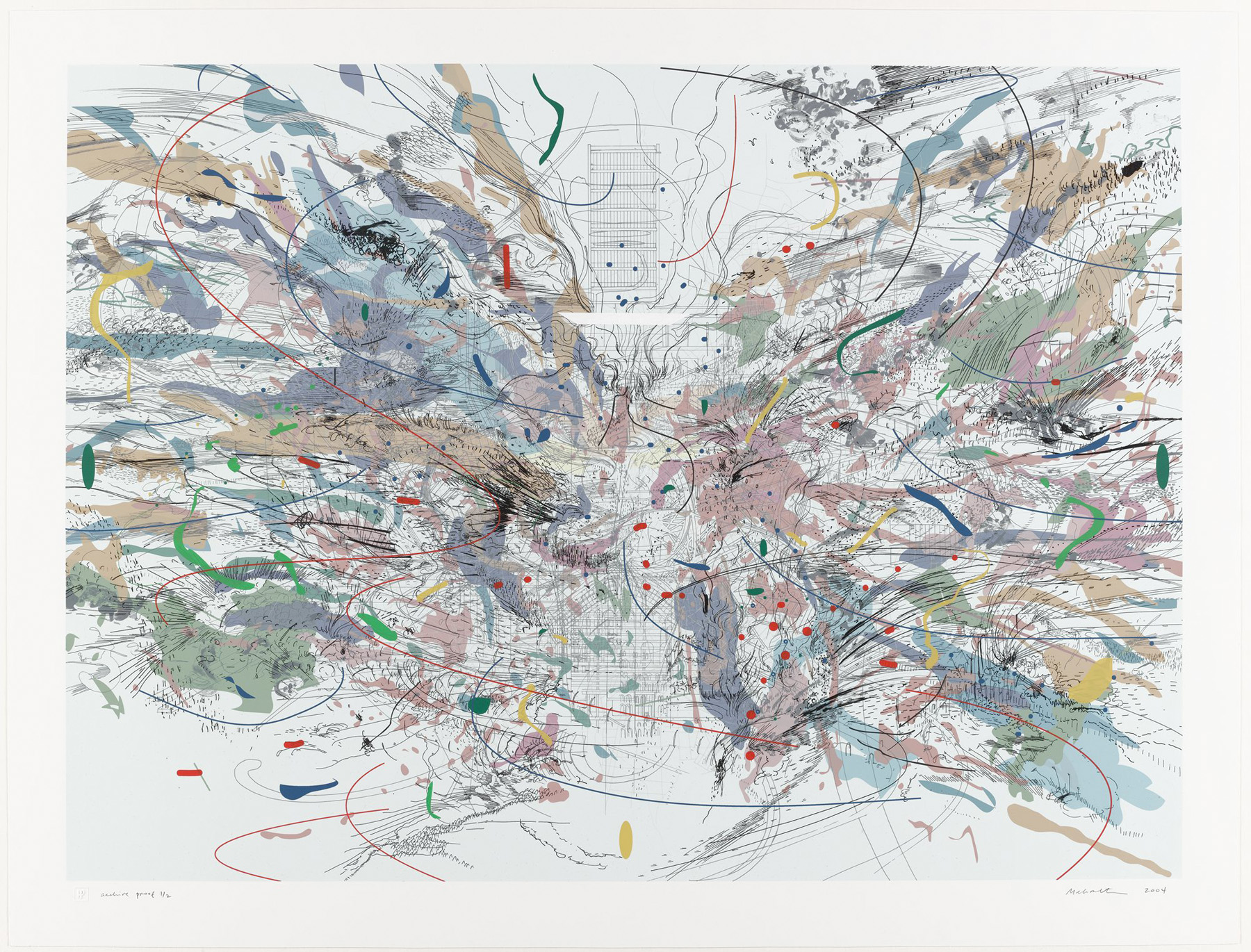

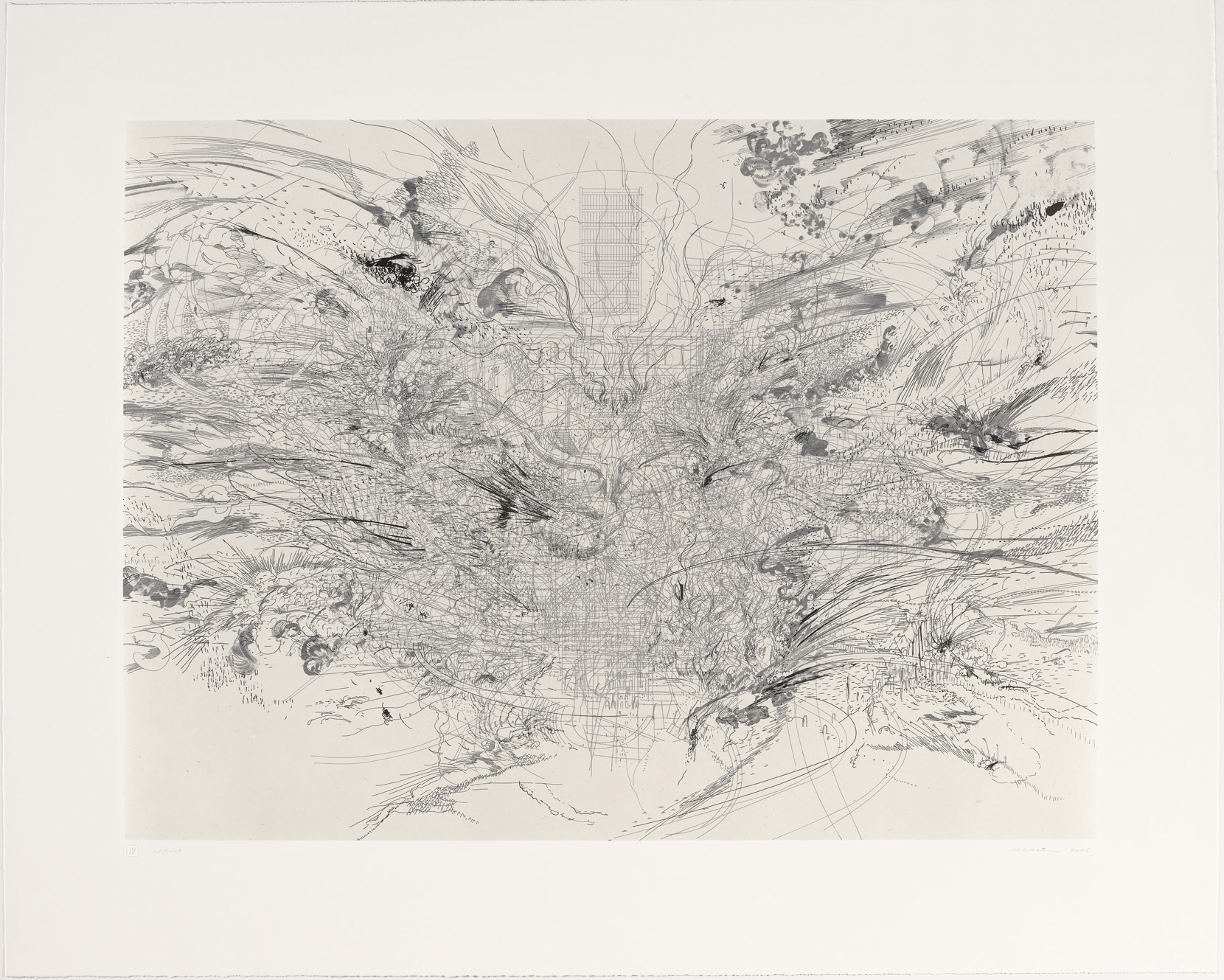

One such workshop introduction by Walker Art Center curator Siri Engberg would lead to Highpoint Editions’ first runaway market success, a pair of semiabstract mixed-media prints by the acclaimed Ethiopian-born artist Julie Mehretu . In 2002, Mehretu began a year-long residency at the Walker, which culminated in a solo exhibition of her drawings and paintings presented there in spring of 2003.30 Concurrently, Mehretu began what would become a nearly three-year collaboration with Rogers and Zac Adams-Bliss, Highpoint’s senior printer, who had recently joined Rogers’s workshop team.31 At Highpoint, Mehretu produced the semiabstract thirty-two-color screenprint and lithograph Entropia (review), 2004 (cat. no. 191) , together with a related tonal lithograph Entropia: Construction, 2005 (cat. no. 192) .32 Both prints reflect Mehretu’s long-standing interest in using imagery derived from the built urban environment as a conceptual framework for exploring global issues of social and political power, particularly how power is wielded to shape personal and communal identity.

Visually and technically complex, the prints combine bits of maps, diagrams, plans, and architectural renderings of socially charged places—streets, plazas, airports, government buildings, schools, parks—with Mehretu’s personal language of signs and symbols.

She calls these layered, multidimensional compositions “psycho-geographies,” essentially dynamic visual expressions of contemporary experience.33 Copublished with the Walker Art Center, Mehretu’s print editions were a critical and commercial success, with impressions acquired by major museums and private collectors alike, providing Highpoint Editions with a much-needed infusion of capital and an immediate boost in its national profile.34 Rogers recalls an early conversation with Mehretu, who at the time had previously made only a handful of prints: “When she arrived at Highpoint, Julie said, ‘How many colors can I do?’ I said, ‘Well, we’ve got skin in the game. As far as I’m concerned, you can do as many colors as you want. I want you to love this print. I want this to be something that you’re really proud of . . . if you’re proud of it, then I know it’ll be great.’”35 Rogers’s trust in Mehretu was well placed. Entropia (review) ranks among Highpoint’s most successful projects.36

Building on Success

The release of Entropia (review) in the fall of 2004 coincided with Highpoint Editions’ inaugural appearance at a national art fair—the Editions/Artists’ Books Fair—an annual event staged in New York’s Chelsea neighborhood gallery district that promoted itself as a “premier showcase for new and contemporary prints, multiples and artists’ books.”37 Popular with collectors and museum curators, the E/AB, as it is known, offered Highpoint the chance to expand its print market and burnish its fledgling brand within the art world and an international community of publishers. For Highpoint Editions, the 2004 E/AB served as a “coming-out party” of sorts, a declaration of confidence in the quality and importance of its publications. The display of Entropia (review) alone in Highpoint’s booth created a buzz that proved invaluable.38 Since then, Highpoint has shown at national art fairs in New York, Baltimore, Cleveland, Chicago, London, and elsewhere.

In 2005, Rogers invited several national and Minnesota artists to collaborate at Highpoint. These included Joel Janowitz , a Boston painter and watercolorist known for his ability to instill a dreamlike, meditative mood into a realistic setting. Over three years, he produced several series in lithography and monotype on the themes of dog parks and greenhouse interiors (cat. nos. 168–78) , the latter inspired by the greenhouses at Wellesley College, in Massachusetts, where he once taught. In these works, lighting and color are exaggerated or muted to an unnatural degree, evoking the humid, misty air, the thriving plant life—and memories of other places and times.39 “Within this structure I have found a visual metaphor for the simultaneity of multiple ways of seeing,” Janowitz says, “as well as for the many filters through which we see and understand the world.”40

Minnesota artists Clarence Morgan and Carolyn Swiszcz also began their Highpoint collaborations in 2005. Encompassing painting, drawing, and printmaking, Morgan’s practice focuses on abstraction, often inspired by nature and systems of order and chaos.41 For his initial collaboration (he returned in 2012), Morgan combined lithography, intaglio, and screenprinting to produce elaborate biomorphic abstractions that suggest microscopic organisms or alien life forms (cat. nos. 194–201) . Swiszcz’s work with Rogers (2005–6, 2017–18) produced a pair of editioned prints (cat. nos. 288–89) , along with a related series of hand-colored and watercolor monoprints (cat. no. 290) . The works develop a favorite Swiszcz subject, which she finds by scrutinizing the urban and suburban architectural landscape for the mundane and often inelegant monuments of daily life.42 Also in 2005, Rogers was printing the second of Mehretu’s prints, Entropia: Construction (cat. no. 192) , a project he had suggested to complement the artist’s first print.

Meanwhile, it was becoming apparent to Rogers and his workshop staff that the Lyndale Avenue facility was too small to accommodate their ambitious visiting-artist program.43 A principal problem was that the Highpoint Center programs—professional shop, artists’ cooperative, educational classes—occupied the same space. The arrangement was meant to encourage camaraderie and feedback among fellow artists—the sort of interactions Rogers had always dreamed of. But in its effort to treat the professional shop and the artists’ co-op in an egalitarian way, Highpoint had overlooked another need: a discrete studio where visiting artists could work quietly, in private, and without interruption. As Highpoint’s print projects grew in scale, the workshop’s space deficiencies grew obvious as well.

In the mid-2000s, as Highpoint Editions’ national reputation continued to rise, several high-profile artists arrived to collaborate with Rogers and his workshop team. Primarily active as painters and sculptors, these included Santiago Cucullu , Cameron Martin , Jessica Rankin , Rob Fischer , and Adam Helms .

Argentinean-born artist Cucullu , who is now based in Milwaukee, is best known for his vibrant—and sometimes disruptive—murals and multimedia installations that combine historical, political, and cultural references with evocations of the personal and autobiographical.44 Arriving at Highpoint in 2005 for what would be the first of several collaborations, Cucullu proposed an ambitious 9 x 9-foot composite print in lithography and screenprinting that would be among the workshop’s largest published artworks. Each of the twelve panels of Architectonic vs. H.R. (cat. no. 90) suggests flashes of memory or historical snapshots, all linked together in a maze of rainbow color. The fragmented imagery is based on Cucullu’s own sketches and photography, which he uses to document the things he finds inexplicable or bizarre in everyday life. As part of the project, which was issued as a boxed portfolio, Cucullu also produced a 4 x 5-foot one-color woodcut printed on cotton muslin, At the Movies (cat. no. 91) , meant to accompany the composite print. Despite harboring some reservations about the work’s scale (and sales potential), Rogers and his team editioned the prints to the artist’s specifications. As a bit of insurance, Rogers suggested that the black-and-white lithographic portion of the composite panels be printed and editioned separately (cat. nos. 94–103) . To his surprise, the composite print sold briskly, while the smaller lithographs were less successful.45 In all, Cucullu produced nearly two dozen editioned prints in a range of techniques.

Martin , known for his conceptual landscape paintings, produced a thirty-nine-color screenprint entitled Conflation, 2006 (cat. no. 183) , an idiosyncratic interpretation of Mount Rainier, which dominates the landscape near Seattle, the artist’s birthplace. With its unnatural color scheme and graphically distilled appearance, Conflation serves as a critique of the increasing containment and commodification of nature.46 The Australian-born Rankin came to Highpoint Editions in 2006 on the recommendation of Julie Mehretu, Rankin’s partner at the time. Known for her elaborate tapestries embroidered with texts, maps, landscapes, and charts, Rankin produced a pair of delicate mixed-media prints (cat. nos. 246–47) that function like pages from a surreal, pictorial diary, in which language, conscious thought, and unconscious reflection commingle.47

Fischer , who was born and raised in Minnesota but now lives in New York City, is best known for sculptures and assemblages composed of found materials.48 For his Highpoint project, he produced one of the workshop’s largest prints—Dodgeball (2008) (cat. no. 145) —a diptych printed in relief and intaglio from sections of reclaimed oak flooring. Snippets of color screenprinted on the print’s surface recall the painted lines on school gym floors, the customary setting for the once-ubiquitous game of dodgeball.

Soon after the release of Dodgeball in August 2008, the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, each acquired an impression. Though subsequent sales were modest (partly due to the diptych’s large size), museum placements such as these were critical for growing Highpoint’s national reputation. Indeed, the implicit endorsement of Highpoint Editions by the Walker and the Whitney, two of the country’s leading contemporary art museums, was invaluable, lending both Rogers and the workshop important credibility.

During his four-month Highpoint collaboration, Brooklyn-based Helms

created two formally and conceptually inventive editions, including Untitled Landscape (2008), (cat. no. 157)

, a mixed-media triptych composed of a flag-like color screenprint on nylon and two photolithographs that juxtapose images and emblems of organized rebellion. He also produced Untitled Portrait (2009) (cat. no. 158)

, a photogravure merging portraits of William “Bloody Bill” Anderson, the Confederate guerrilla active during the American Civil War, and the Argentinean Marxist revolutionary Ernesto “Che” Guevara into a single emblematic “rebel” figure. Both projects grew out of Helms’s long-standing interest in exploring violent or fringe political groups and subcultures, past and present.49

State of the Art

In 2007, convinced that Highpoint’s Lyndale Avenue facility could no longer accommodate the organization’s vision, its leadership and board began looking for a larger home in Minneapolis.50 Although an industrial site might have been less expensive and perhaps better suited to the mechanics of print production, it was agreed that, to more easily connect with the community, the new building would be in an active commercial district.51 It would allow for expansion. And, ideally, Highpoint would own the building.52 As it happened, the relocation effort was launched during the Great Recession (2007–9),53 which promised to make fundraising appeals, grant opportunities, and real estate financing options more challenging. Undaunted, McGrath, Rogers, and board members began their search. One possibility was Northeast Minneapolis, increasingly recognized as a bona fide arts district: since the 1990s, hundreds of working artists had moved into repurposed industrial and commercial buildings there, along with galleries and art centers. Then, Highpoint learned of an opportunity to acquire a 10,000-square-foot commercial building on West Lake Street in the Lyn-Lake neighborhood of South Minneapolis. Formerly a retail bookstore,54 the building’s location on a major business corridor within blocks of the bustling Uptown commercial district was well suited for Highpoint’s needs, not least its core mission of public engagement. Despite a hefty price tag, Highpoint Center purchased the building in 2008.55

To redesign the interior, Highpoint approached the architecture firm James Dayton Design, known for its innovative designs for the MacPhail Center for Music in Minneapolis, and the Minnetonka Center for the Arts in nearby Wayzata, Minnesota. With his penchant for natural light, flexible spaces, and unadorned industrial materials, Dayton, who had trained with the renowned American architect Frank Gehry, was the ideal choice to create a community-based printmaking center.56 Opened in October 2009, the new Highpoint Center for Printmaking was more than three times larger than its former home and featured an expanded state-of-the-art professional shop, dedicated spaces for the artists’ co-op and a studio classroom, a visiting-artist studio, a print study room, a reference library, and exhibition galleries overlooking Lake Street. In a nod to environmental stewardship, Highpoint commissioned the Minnesota-based artist Kinji Akagawa to design a rain garden to capture its rooftop runoff.

With its expanded workshop and increased production capacity, Highpoint Editions was poised for growth. Several projects begun at the Lyndale Avenue facility resumed at the new professional shop, including a two-year collaboration with the prominent Mexican-born interdisciplinary artist Carlos Amorales , whom Rogers had recruited after visiting the artist’s Mexico City studio.57 Known for his eclectic subject matter and conceptually based practices, Amorales worked closely with Rogers and his printing staff to produce more than two dozen editioned prints that were completed in 2010 (cat. nos. 2–23) .

Issued in suites and multiple-panel configurations, the prints feature imagery Amorales selected from his Liquid Archive, a digital database of more than 1,500 silhouetted vector graphics he compiled from an extensive range of sociopolitical, cultural, and personal sources.58 The vector graphics were then rendered as laser-cut acrylic printing plates—birds, a monkey, human figures, world nations, and abstract forms—and printed and merged to form large-scale composite images. By altering, combining, and reinterpreting existing images, Amorales stripped the forms of their original context and associated meanings, while creating the potential for new connotations and viewer-driven interpretations.59

As Highpoint’s artistic director and master printer, Rogers made it a priority to accommodate the conceptual and material working methods of Highpoint’s visiting artists, allowing them to freely explore printmaking’s creative possibilities as part of the collaborative process. “I’m a technician who’s there as kind of a safety net for the artist, not running the show,” Rogers explains. “I’m there to help and collaborate not direct. My philosophy for the artist is: get in there and experiment, make messes, and let’s go places you didn’t know when you walked into the studio this morning. If something fails, at least the artists know they’ve got somebody who’s on their side and willing to take risks on their behalf.”60 Such was the case with Amorales, whose editioned prints challenged Rogers and his team with their sheer technical complexity and need for precise uniformity when building composite images from small, acrylic printing matrices that must be repeatedly repositioned on the paper, sometimes more than 150 times. Boldly original, the Amorales prints reinforced Highpoint’s growing reputation as an intrepid and innovative print workshop.

During the next several years, Highpoint continued to garner national attention with the release of editioned prints by such prominent artists as Chloe Piene, Carter, Willie Cole, Sarah Crowner , and Aaron Spangler. All were known for their innovative multidisciplinary practices, something Rogers considered a boon to inspired printmaking. He would not be disappointed. With subjects ranging from figural to abstract to conceptual, the prints reflected the artists’ unique creative perspectives that expanded Highpoint’s publication diversity.

Piene arrived at Highpoint in the fall of 2009, just as the new Lake Street facility was preparing its public debut. Based in New York and Berlin, she is renowned for her delicate yet powerful figurative drawings that dissect the external and internal structures of the body.61 Prior to her Highpoint collaboration, Piene had produced only one editioned print, an etching. But at the suggestion of Rogers, she discovered the pleasure of drawing on the surface of polished limestone block, creating a series of lithographs of skeletal figures, printed in black on layered sheets of translucent Japanese paper (cat. nos. 242–45) . The technique generated delicate variations in tone and surface, imparting a luminous, ethereal quality that heightens their deliberate ambiguity.

In 2010, New York–based conceptual artist and filmmaker Carter

began a two-year collaboration with Highpoint, producing a series of semiabstract prints in lithography and screenprinting (cat. nos. 37–40)

. Much like his paintings, the prints feature intricately layered assemblages of seemingly disparate imagery—drawings, doodles, diagrams, and found photographic material. Though at times puzzling, Carter’s conceptually complex imagery functions as a separate reality, challenging conventional ideas of human identity, social relationships, and visual and psychological perception.62

Ten Years On

The release of Carter’s prints in 2011 coincided with the tenth anniversary of the founding of Highpoint Center for Printmaking, a milestone the center observed with various community-centered festivities and a major fundraising appeal. Appearing in conjunction with Highpoint’s celebrations was the retrospective exhibition Highpoint Editions—Decade One organized by the Minneapolis Institute of Art. The exhibition presented highlights from Highpoint Editions’ first ten years of print production and debuted as part of the museum’s fall exhibition lineup.63 Besides displaying the work of prominent contemporary printmakers, Mia’s show provided invaluable validation of Highpoint Editions’ standing among nationally recognized print workshops. An abbreviated version of the exhibition later traveled to Boston University, where it was shown in conjunction with the 2013 Boston Printmakers North American Print Biennial.

One of Highpoint’s most memorable endeavors was with New Jersey native Willie Cole. Long a fan of the artist, Rogers made sure Cole was one of the first artists he invited to Highpoint, but it wasn’t until a decade later, in 2011, that Cole could accept the invitation.64 He is perhaps best known for assemblages, sculptural works, and prints that explore the metaphorical potential of everyday objects in addressing themes of African American culture, history, and experience. In feats of creative alchemy, he decontextualizes items such as women’s shoes, steam irons, ironing boards, bicycle parts, and hair dryers, and transforms them into conceptually complex—and often humorous—artworks.

At Highpoint, Cole relied on his steam iron and ironing board motifs for all but one of his forty-eight editioned prints (cat. nos. 41–88) .65 In his mind, these objects suggest a range of symbolic associations, including ships of the transatlantic slave trade, tribal shields and masks, and domestic labor by women of color. The screenprint series “Complementary Soles” (cat. nos. 69–77) , based on the bottom, or sole, of a steam iron, are rendered in eye-dazzling color contrasts that, according to the artist, represent various aspects of human awareness.66 In his suite “The Virgins” (cat. nos. 78–85) , Cole adapts a similar motif, though on a larger scale, to evoke the Virgin of Guadalupe, the celebrated sixteenth-century icon of the Virgin Mary, mother of Jesus Christ, so venerated in Mexico.

“The Beauties” (cat. nos. 41–63) and closely related “Five Beauties Rising” (cat. nos. 64–68) , both released in 2012, crown Cole’s remarkable creative output at Highpoint (see Jennifer L. Roberts’s essay on “The Beauties” in this catalogue). Each intaglio and relief print is based on a different metal ironing board found locally and then crushed and battered by Highpoint staff. Flattened and bruised, they served as unconventional double-sided printing matrices for transferring ink to paper. For Cole, the boards symbolize the drudgery and hardship of domestic servitude; the names assigned to each print, many belonging to relatives, collectively memorialize female ancestors who were enslaved or toiled in domestic service.67 With their gray tonalities and distinctive patinas, the prints appear luminous, even ghostlike. This is not accidental. The artist has signaled that these mysterious prints are intended to commemorate past lives and neglected histories. Indeed, the sheets’ tall, narrow shape and abraded appearance recall ancient stone monuments or weathered tombstones, traditional means of marking or measuring one’s life. Released as a related body of work, Cole’s prints proved to be a critical and commercial success, extending Highpoint’s string of standout publications.

On the heels of this extraordinary creative and technical partnership, Rogers turned to the prominent Minnesota-based artist Aaron Spangler , known for intricately carved wood sculptures and frottage drawings that allude to often unnoticed aspects of American life.68 Beginning in 2012, he produced “Luddite,” a suite of ten woodblock prints whose subjects draw mostly from life in north-central Minnesota and Christian homesteaders seeking refuge from mainstream culture (cat. nos. 276–85) . Working on planks of locally milled basswood, Spangler wove elements of the real and the surreal into complex amalgamations. Each of the hand-printed woodcuts is informed by Spangler’s intuitive, self-taught working method—a carving process that for the artist is also an act of discovery.69 “Each of these pieces stand on their own, tied to a specific thought,” he says. “But as is consistent with most of my work, themes of rural chaos, high anxiety, political outrage, nature’s beauty and bounty, stoicism, severe religion, wellness, and spiritual bliss play themselves out.”70

Meanwhile, renowned artist Jim Hodges arrived in Minneapolis to begin what would become Highpoint’s longest collaboration (2013–19)—and one of its most challenging. A native of Washington State, Hodges grew up close to nature, a fact that has long informed his work. Another common thread within his wide-ranging practice, which includes sculpture, painting, found-object installation, and printmaking, is the poetic consideration of life’s many mysteries, including birth, death, love, and the inevitability of change.71

For his Highpoint project, Hodges created a suite of four mixed-media prints called “Seasons” (cat. nos. 159–62)

. For him, the seasons symbolize cycles of growth and decay, the inevitable change and renewal that define life. Though strongly abstracted, each print captures an essential quality of its respective season, a fleeting moment that evokes our own memories and experiences. According to Rogers, the material complexity and technical hurdles derived from Hodges’s creative process. “Jim is a very intuitive worker,” Rogers explains. “He tends to tear things up, tape them back together, draw on them, cut them, or destroy them, all in search of the essence of the print. Since his process is nonlinear, we basically had to reverse engineer everything once he arrived at his idea.”72 Copublished by Highpoint Editions and the Walker Art Center, “Seasons” was issued as individual editions between 2015 and 2019 to considerable acclaim.73

Expanding the Roster

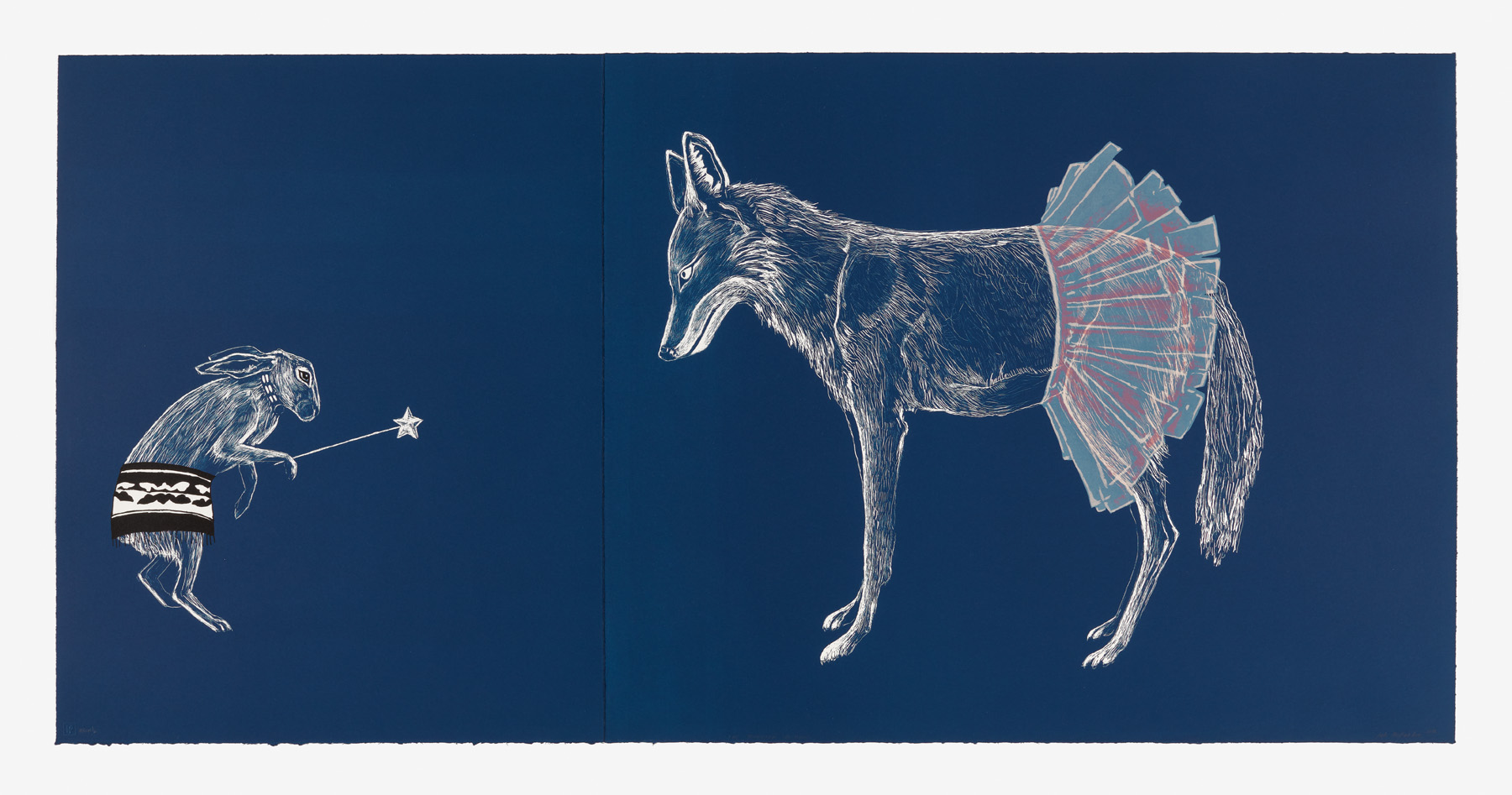

In 2014, as Highpoint marked its fifth year in its new facility, Rogers ramped up his efforts to attract top talent who would expand the scope of contemporary printmaking. He invited St. Paul–based painter Julie Buffalohead to be a visiting artist. Her work was well known among Minnesota collectors but had only recently received national attention. A member of the Ponca Tribe of Oklahoma, Buffalohead is a visual storyteller who draws on her Indigenous heritage, personal life, and popular culture to examine issues of cultural identity, assimilation, social injustice, and intercultural interactions.74 At Highpoint, Buffalohead created nearly a dozen editioned prints in lithography and screenprinting (cat. nos. 24–34) , each a narrative featuring one or more animal protagonists—deer, coyotes, rabbits, crows, squirrels, mice—whose actions and attributes serve to deconstruct myths and offer new ways of thinking about Indigenous cultures. (See Jill Ahlberg Yohe’s essay on the work of Buffalohead, Andrea Carlson, Brad Kahlhamer, and Dyani White Hawk in this catalogue.) Rich in symbolism and exacting detail, the prints proved immensely popular, with many editions selling out within days.

While Buffalohead completed her residency, Rogers next invited Minneapolis-based artist Jay Heikes to make prints at Highpoint. Like Buffalohead, Heikes was well regarded locally. He had also established a national following for his innovative sculptures, drawings, and installations centered on themes of metamorphosis, transcendence, and material transmutation.75 At Highpoint, he produced a body of editioned and unique prints in lithography and screenprinting collectively titled Niet Voor Kinderen (Not for Children) (cat. nos. 148–55) . First, he made a series of semiabstract photograms by placing objects on photosensitive material and briefly exposing them to light, producing eerie silhouettes. He then separated the images into three groups—corresponding to heads, torsos, and legs—so they could be recombined to resemble human figures. The tripartite prints recall the surrealist parlor game Exquisite Corpse, in which participants draw a figure on a sheet of paper folded so that each cannot see what the others have drawn until the image is complete. Revealing his fascination with material experimentation, Heikes used asphaltum, a brownish-black, tar-like substance normally used as a masking agent in etching, to ink some unique screenprints. The substance was also used by ancient Egyptians in mummy preparation, an association well suited to Heikes’s “corpse” imagery. Because the unorthodox material is toxic and posed concerns for Highpoint’s printers and equipment, Heikes printed them off-site in his private studio.

In 2015, Highpoint Editions received word that it would be admitted to the International Fine Print Dealers Association (IFPDA), a New York–based trade organization of art galleries, print publishers and workshops, and private dealers who specialize in marketing fine art prints and editions.76 For many years, IFPDA membership excluded nonprofit organizations, including Highpoint Editions, in the belief that they had competitive advantages over commercial businesses. But member-dealers sympathetic to Highpoint and familiar with the quality of its publications successfully lobbied for a rule change. For Highpoint, IFPDA membership represented a major seal of approval within the contemporary print market and new opportunities to reach a worldwide market.

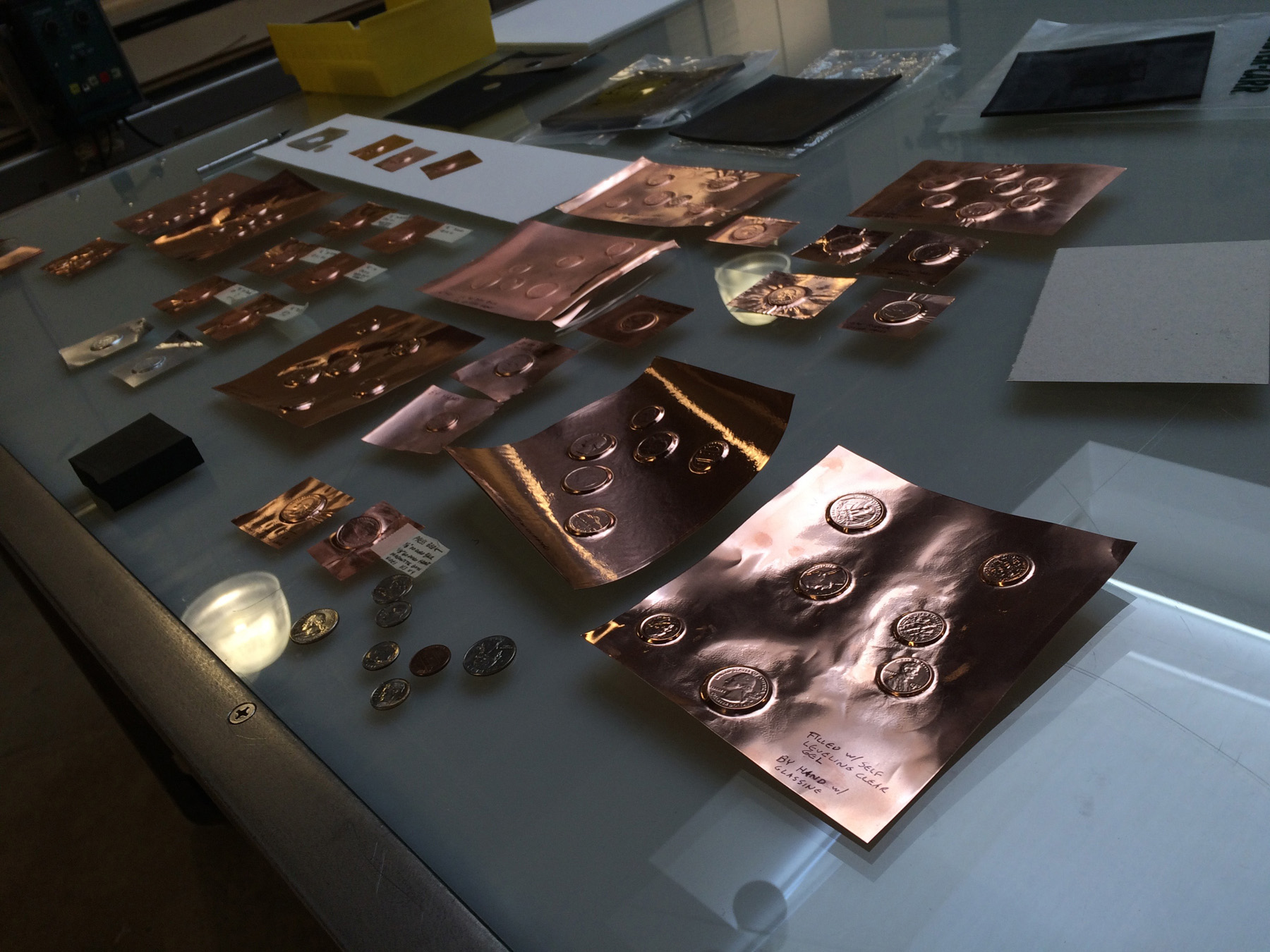

In the mid-2010s, Highpoint Editions worked with some heavy hitters, completing workshop residencies with Do Ho Suh and Mungo Thomson . Highpoint favorite Todd Norsten returned for new projects, as did Carolyn Swiszcz. Thomson, a conceptual artist based in Los Angeles, proposed what would become Highpoint Editions’ first publishing venture involving three-dimensional works known as multiples. Ever open to artist-driven expression, Rogers embraced the technical challenge posed by Thomson’s project, namely embossed metallic foil. Each sheet in the series “Pocket Universe” (cat. nos. 293–94) depicts randomly arranged coins (retrieved from Thomson’s pocket) embossed on either copper or aluminum foil, a technique Rogers engineered with the aid of a lithography press.77

With their pristine reflective surfaces and detailed impressions of pennies, nickels, dimes, and quarters, the embossed designs resemble constellations or planets. The series title refers to a concept proposed by the American theoretical physicist Alan Guth, who postulated the possibility of sparking cosmic inflation inside a hypothetical laboratory, thus generating a “pocket universe” that would exist within another existing universe.78 Thomson’s whimsical play on words equates Guth’s hypothetical laboratory with Highpoint’s very real printmaking studio.

Argentinean-raised artist Alexa Horochowski

, now a sculpture professor based in Minnesota, made what is perhaps the most unconventional of the workshop’s published works. With the aid of barrel fans, disposable items, and various media, she produced a series of monumental abstractions called “Vortex Drawings,” 2017 (cat. no. 167)

to showcase the problem of nonbiodegradable trash in the world’s oceans.79 Working off-site at the Soap Factory, a now-defunct experimental art center in Minneapolis, she first assembled commercial-grade barrel fans to create an artificial wind vortex. Then she gathered Styrofoam cups, polystyrene packing peanuts, aluminum cans, and other trash, coated them in substances such as graphite, ink, acrylic, linseed oil, and pigments, and placed them on assorted papers or Tyvek (a synthetic polyethylene material) within the vortex. When the wind blew the debris, the various coatings left gesture-like marks on each sheet. The resulting artworks blend aspects of drawing and printmaking. They also involved a high degree of chance, making each vortex drawing unique. Like much of Horochowski’s work, they are informed by conceptual and performance art, and effectively touch on the issues of environmental degradation and mass consumerism while displaying a formal elegance that belies their mechanical pedigree.

Commitment to Diversity

Over the past several years, Highpoint Editions has renewed its long-term commitment to diversity and inclusion by increasing representation of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) artists in workshop residencies. These efforts align with Highpoint’s organizational values and community-based mission, and—equally important—correspond with Rogers’s desire to continually expand the conceptual, expressive, and aesthetic breadth of the workshop’s publications. In consultation with BIPOC artists and community members, Highpoint’s curatorial committee, and alumni of the visiting-artist program, Rogers recruited several prominent artists to partner with Highpoint, including Andrea Carlson, Rico Gatson, Brad Kahlhamer , Dyani White Hawk, Delita Martin, and Njideka Akunyili Crosby.80 Regardless of their printmaking experience, each brought a distinctive creative expression to the workshop. Chicago-based Carlson draws from her Anishinaabe, French, and Scandinavian heritage to examine issues of cultural identity, historical revisionism, institutional authority, and the loss of Indigenous practices, languages, and art forms.81 In her editioned screenprints Anti-Retro, 2018 (cat. no. 35) , and Exit, 2019 (cat. no. 36) , she used fictional, symbol-laden landscapes to expose fraudulent cultural narratives and reframe popular (collective) memory. Carlson’s storytelling approach can be likened to Buffalohead’s critical examinations of Indigenous experience, while her deep exploration into the historical roots of neocolonial supremacy offers something of a road map for those seeking greater intercultural understanding.

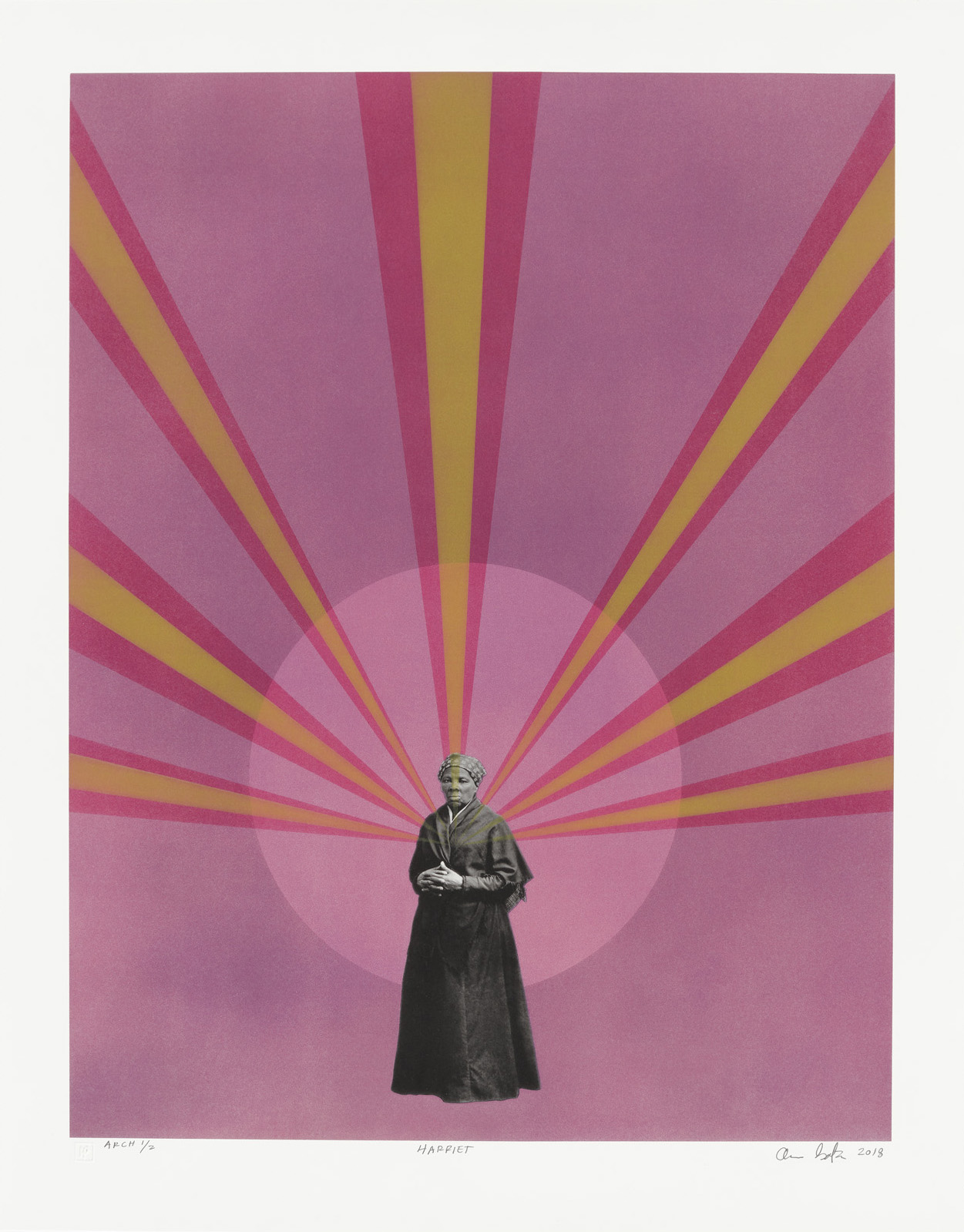

Gatson , a multidisciplinary artist based in Los Angeles, explores issues of Black consciousness, identity, and sociopolitical power dynamics.82 In his mixed-media print Harriet, 2018 (cat. no. 146) , he presents Harriet Tubman, the American abolitionist and political activist known for her efforts to free enslaved persons using the Underground Railroad network of safe houses. The portrait is part of Gatson’s long-running “Icons” series, which celebrates prominent Black civil rights advocates, writers, musicians, actors, and sports figures. In these works, Gatson often combines existing black-and-white photographs with radiating lines of brilliant color that symbolize centers of power. “I was thinking early on about these figures as superheroes,” he explains. “As the series progressed, they became literally icons—the halos and lines are graphic representation of energy coming out of them. The most important part for me is feeling.”83

The graphic symbolism is powerfully original—portraiture as a form of political activism. In 2017, as Gatson was developing his homage to Harriet Tubman, he began a second editioned print, Untitled (Cotton Pickers) (cat. no. 147) , which features found images of African American farm laborers set within a loosely arranged grid of colored circles and ellipses. The color scheme (red, yellow, green, orange, and black) is frequently associated with Pan-Africanist ideology and alludes to the African heritage of southern sharecroppers and enslaved plantation field hands. For various reasons, the print’s release was delayed until the fall of 2021.

In 2019, Minneapolis-based artist Dyani White Hawk began an intensive, eight-month collaboration with Rogers and his workshop team. Born of Sičáŋǧu Lakota, German, and Welsh ancestry and raised within Native and non-Native communities, White Hawk has developed a wide-ranging artistic practice that includes painting, sculpture, photography, video, installation, and performance art. Seeking to position Indigenous art within the history of modern and contemporary American art, she draws inspiration from her own cross-cultural experiences and often blends the visual language of twentieth-century abstraction and traditional Lakota art forms.84

For her Highpoint collaboration, White Hawk conceived a suite of four boldly colored, life-size interpretations of women’s ceremonial dentalium-shell dresses. Realized as screenprints and embellished with metallic foil, the prints, titled “Takes Care of Them,” 2019 (cat. nos. 295–98)

, originated from the practice of asking military veterans to stand in each of the four cardinal directions (north, south, east, west) for protection during the wablenica (orphan) ceremony, a ritual welcoming those separated from family and heritage back into the tribal community.85 Each print represents a quality that women contribute to the community: Wačháŋtognaka (Nurture), Nakíčižiŋ (Protect), Wókaǧe (Create), and Wówahokuŋkiya (Lead). Aesthetically and conceptually, the dresses exemplify White Hawk’s creative concerns while encouraging intercultural dialogue and understanding. The set has proven to be exceptionally popular, with multiple museums acquiring it for their permanent collections.

Facing Challenges

The coronavirus public health crisis that unfolded in early 2020 profoundly disrupted daily activities around the world. Mandated lockdowns and other mitigation measures that followed contributed to a decline in the global economy; many businesses, including arts organizations, did not survive. The pandemic forced the Highpoint Center for Printmaking to close its doors for an extended period before restoring limited public access, resulting in significant financial setbacks and staffing challenges. Online print fairs, virtual exhibitions, and other digital marketing efforts provided some print sale revenue, but workshop production was sharply curtailed, and visiting-artist residencies suspended.

The May 25, 2020, murder of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, by a white Minneapolis police officer attracted global attention and triggered demonstrations locally and worldwide. The rioting and civil disobedience unleashed in Minneapolis–St. Paul extended to the Lyn-Lake neighborhood where Highpoint is located. Despite major property losses in the area, the Highpoint building sustained only minor exterior damage. The emotional and spiritual damage to the local community, however, would be profound and long-lasting.

Despite the many challenges of 2020, the year ended on an optimistic note when the Minneapolis Institute of Art announced it had acquired the complete archive of Highpoint Editions for its permanent collection.86 Representing twenty years of workshop production (2001–21), the archive consists of more than 325 unique and editioned prints and multiples, along with more than one thousand items of ancillary production material: preliminary drawings, working and trial proofs, progressive proof sets, color tests, “false starts” (unrealized projects), and printing plates and blocks. Long a goal of Highpoint, the placement of its twenty-year archive at a major art museum ensures that its legacy will be permanently preserved and be made available to a broader audience through exhibitions, publications, and public access in Mia’s print study room. To showcase Highpoint Editions’ publication history, Mia mounted “The Contemporary Print: 20 Years at Highpoint Editions” in October 2021, to coincide with Highpoint’s twentieth anniversary. Concurrently, Mia launched a digital catalogue raisonné of the archive accessible on the museum’s website.

Twenty Years On

In the spring of 2021, as the coronavirus pandemic began to ebb, Rogers and his workshop staff resumed work on several pending projects, including “Keepsakes,” a suite of mixed-media prints by Delita Martin . These feature hand-drawn likenesses of children superimposed on textured images of antique christening dresses collected by the artist (cat. nos. 184–190) . Martin then added hand stitching to each print, signifying the home-based skills she learned from her grandmother as a child. For Martin, merging traditional techniques and materials evokes ancestral memory, engendering a formal and conceptual dialogue that she uses to reconstruct the collective identity of Black women.87

As Highpoint Editions marks its twentieth year, it is natural to reflect on its extraordinary progress. In less than a generation, it has grown from a modest storefront operation to a nationally prominent printer and publisher of fine art prints. Today the workshop’s diverse roster of collaborators includes some of the most highly accomplished contemporary artists in the world. Their contributions to contemporary printmaking are significant, made possible by master printer Rogers’s abiding commitment to creative risk taking and synergetic problem solving. Indeed, measured by the quality and impact of its publications, Highpoint Editions stands as a leader among contemporary American print workshops.

The story of Highpoint Editions is above all a story of people. It is the story of cofounders Carla McGrath and Cole Rogers, who had the courage to imagine a flourishing community-based arts organization dedicated to the art of printmaking, and the resilience to guide its growth despite myriad challenges. And it is the story of dedicated individuals who embraced the founders’ vision and lent their expertise to build a first-rate printmaking center from the ground up. From artists and workshop printers to the professional staff and board of directors to collectors and financial supporters and the many art enthusiasts and community partners, it is their collective devotion to contemporary printmaking that lies at the heart of Highpoint’s success. Over the past twenty years, Highpoint Editions has expanded the boundaries of contemporary printmaking through its innovative creative collaborations among the artists and workshop printers. Indeed, it is this shared creative vision, one anchored in tradition, that remains the hallmark of Highpoint Editions.

Notes

Highpoint Center for Printmaking was incorporated as a Minnesota nonprofit organization in 2000. Located at 2640 Lyndale Ave. S., in Minneapolis, the center opened to the public in the spring of 2001 but delayed its “grand opening” celebration until October 29, 2001. Highpoint occupied a portion of a commercial building owned by the Soo Visual Arts Center (Soo VAC), which at the time was also a co-occupant of the building. ↩︎

In contemporary practice, collaborative printmaking involves an artist and a master printer working together to produce original prints, usually realized as an edition, although unique prints (monoprints, monotypes) may also be produced. Each party contributes specialized skills, knowledge, and insight to the project as required. Generally, the artist creates an image directly on a printing matrix, such as a lithographic stone, intaglio plate, or woodblock. Images may also be transferred to a matrix by photographic or mechanical means. The printer prepares and proofs the printing matrix, making corrections and adjustments in consultation with the artist, and produces a final proof impression for the artist’s approval. The artist acknowledges approval by signing the final proof impression, which is generally known as a bon à tirer (good to print) or BAT proof. Using the BAT proof as a guide, the printer, often aided by assistants, then produces a uniform edition of impressions, which may or may not include additional proofs designated for the artist’s or printer’s personal use. The artist then signs and typically numbers all the impressions in the edition. ↩︎

An example of the cooperative workshop model is the experimental intaglio printmaking studio Atelier 17, established in Paris in 1927 by the British surrealist artist Stanley William Hayter (1901–1988). Known for its collaborative atmosphere, Atelier 17 was designed to be a nonhierarchical “creative laboratory” where visiting artists would freely exchange ideas on techniques, methods, and aesthetics. A second example of the cooperative model is the Robert Blackburn Printmaking Workshop, a lithography studio founded in New York in 1947 by the artist and educator Robert Blackburn (1920–2003). Established as a space for learning, exchange, and experimentation in the graphic arts, Blackburn’s workshop attracted a diverse creative community from around the world. ↩︎

Grosman established ULAE in the hamlet of West Islip, Long Island, New York. The workshop later moved to its current location in nearby Bay Shore. ↩︎

For an informative history of the rise of the collaborative print workshop and the resurgence of contemporary printmaking in the United States during the 1960s and 1970s, see James Watrous, “Print Workshops Coast to Coast and the Print Boom in the Marketplace, 1960–1980,” in A Century of American Printmaking (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1984), pp. 226–84. ↩︎

Founding director June Wayne established Tamarind Lithography Workshop to reinvigorate the declining art of lithography by extending the medium’s expressive potential, stimulate the market for original lithographs, and train a pool of master printers who would promote collaborative lithography as integral to contemporary art. The press was funded by the Ford Foundation until it moved from Los Angeles to became affiliated with the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, in 1970. ↩︎

McGrath earned her JD degree from Hamline University School of Law (now Mitchell Hamline School of Law), St. Paul, in 1986 and passed the Minnesota bar examination the same year. ↩︎

Minneapolis-based arts attorney John Roth was an early and critical source of expertise in developing Highpoint’s business plan and nonprofit status. Roth later joined Highpoint’s board of directors as a founding member and served for several terms. ↩︎

Cole Rogers, conversation with the author, October 28, 2020. ↩︎

At Highpoint Editions, Rogers used photogravure, photolithography, and photo-screenprinting techniques to replicate photographic images. ↩︎

Carla McGrath, conversation with the author, September 9, 2020. ↩︎

Carla McGrath, conversation with the author, September 9, 2020. The Northern Clay Center, established in 1990, is a Minneapolis-based nonprofit visual arts center that supports and promotes the ceramic arts through education, exhibitions, and artist services. The Minnesota Center for Book Arts, established in 1983, is a Minneapolis-based nonprofit visual arts center that supports and promotes the book arts as a dynamic contemporary art form through education, exhibitions, and artist services. It is the most comprehensive book arts center in the United States. ↩︎

Highpoint Center for Printmaking has received grants for its operating budget and programmatic initiatives from a range of private foundations and governmental agencies, including the McKnight Foundation (Minneapolis), the Jerome Foundation (St. Paul and New York), the Target Foundation (Minneapolis), the Minnesota State Arts Board (St. Paul), and the National Endowment for the Arts (Washington, D.C.), among others. ↩︎

According to the National Assembly of State Arts Agencies in its “State Arts Agency Legislative Appropriations Preview, Fiscal Year 2021,” the state of Minnesota was to appropriate $7.22 per capita in legislative appropriations to state arts agencies. Per capita appropriations for the arts among the other states range from $4.61 (Hawaii) to zero (Arizona), accessed December 4, 2020, https://nasaa-arts.org/nasaa_research/state-arts-agency-legislative-appropriations-preview-fiscal-year-2021/. ↩︎

Vermillion Editions Limited was active from 1977 to 1992. The workshop’s archive is preserved in the permanent collection of the Minneapolis Institute of Art. For more on Rathman’s projects at Vermillion Editions, see Dennis Michael Jon et al., Vermillion Editions Limited: A History and Catalogue 1977–1992 (Minneapolis: Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 2006). ↩︎

For more on Rathman’s subjects and investigations of American masculinity, see Kirk Douglas and Brad Zeller, David Rathman: Stand By Your Accidents, exh. cat. (Rochester, Minn.: Rochester Art Center, 2014). ↩︎

Mia curators acquired two prints by Linda Schwarz: At the Middle of Life , 1994, open-bite etching, Xerox transfer, and woodcut on Japan paper, gift of funds from the Print and Drawing Council, P.94.18; and At the Middle of Life , 1995, color woodcut, etching and Xerox transfer on Japan paper, gift of funds from Julie L. Knoff and the Print and Drawing Council, P.95.6. Both prints were published by the artist. ↩︎

For more on Schwarz’s sources and printmaking practice, see Volker Straebel et al., Linda Schwarz, exh. cat. (Berlin: Hatje Cantz, 1996). ↩︎

In addition to the Rathman and Schwarz print projects, Highpoint Editions arranged contract printing services with the Minneapolis-based artist Stuart Nielsen, who at the time was a member of the board of directors of Highpoint Center for Printmaking. Nielsen produced nine editioned prints under this arrangement (see cat. nos. 211–22). To avoid any potential conflict of interest, Nielsen published the prints himself under the entity Basic Content of Minneapolis. ↩︎

For more on Esch’s narrative-based practice, see Douglas Fogle et al., Dialogues: Mary Esch/Daniel Oates, exh. cat. (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 1997). ↩︎

For more on Norsten’s language-based work, see Philippe Vergne, Safety Club, exh. cat. (Minneapolis: Midway Contemporary Art, 2007). ↩︎

See also Dieter Buchhart et al., Ed Ruscha: Ribbon Words (New York: Edward Tyler Nahem Fine Art, 2016). ↩︎

Cole Rogers, conversation with the author, October 28, 2020. ↩︎

Exceptions were made for the galleries and dealers who represented Highpoint’s visiting artists and for art consultants who received a sales commission for placing Highpoint prints with their private clients. ↩︎

Cole Rogers, conversation with the author, February 19, 2021. ↩︎

Beginning in 2005, Highpoint Editions also published and distributed new-release brochures and exhibition catalogues on the work of collaborating artists as part of its marketing efforts. ↩︎

Highpoint Center for Printmaking’s founding board of directors included Carla McGrath (HCP executive director), Cole Rogers (HCP artistic director and master printer), John Roth (attorney-at-law), Jerry Krepps (professor of studio art, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis), Siri Engberg (curator, Walker Art Center), and the author. ↩︎

Early in its history, Highpoint Center for Printmaking convened an outside advisory committee of experts in contemporary art and print publishing. The committee was later deemed redundant and was discontinued. ↩︎

Several staff members from the Walker Art Center and Minneapolis Institute of Art have served on Highpoint Center for Printmaking’s board of directors, including Siri Engberg, Michelle Klein, Keisha Williams, and the author. ↩︎

“Julie Mehretu: Drawing into Painting” opened at the Walker Art Center on April 6, 2003, and traveled to three additional venues. ↩︎

Zac Adams-Bliss, who graduated from MCAD with a BFA degree in graphic design, began his Highpoint career as a studio intern in 2003 and was promoted to assistant printer in 2004. He currently holds the position of senior printer. ↩︎

Entropia (review) and Entropia: Construction were copublished by Highpoint Editions and the Walker Art Center. ↩︎

For a discussion on the development of Mehretu’s printmaking activities, see Siri Engberg, Excavations: The Prints of Julie Mehretu, exh. cat. (Minneapolis: Highpoint Editions, 2009). ↩︎

Impressions of Mehretu’s Entropia (review) were acquired at the publication’s release by the Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York; the Studio Museum of Harlem, New York; the Philadelphia Museum of Art; the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; the Des Moines Art Center, Iowa; the Minneapolis Institute of Art; and the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis (copublisher). ↩︎

Cole Rogers, conversation with the author, October 28, 2020. ↩︎

In addition to income from print sales and a boost in workshop prestige, Julie Mehretu’s collaboration with Highpoint Editions contributed to the workshop’s goal of greater diversity in gender, race, and sexual orientation. ↩︎

The Editions/Artists’ Books Fair was founded in 1998 by Susan Inglett of I.C. Editions, New York, in partnership with Brooke Alexander Editions and Printed Matter. The fair is now presented by the Lower East Side Printshop, New York, a nonprofit organization. ↩︎

In conjunction with the E/AB Fair, Mehretu’s Entropia (review) was featured in Time Out New York magazine, a leading weekly guide to cultural and entertainment events. ↩︎

For more on the origins on Janowitz’s greenhouse subjects, see Judith Hoos Fox et al., Wellesley Greenhouse: Janowitz, Kumler, Mazur, exh. cat. (Wellesley, Mass.: Wellesley College Museum, 1977). ↩︎

Joel Janowitz, conversation with Mia curator Thomas Rassieur, 2011. ↩︎

For more on Morgan’s biomorphic abstraction, see Clarence Morgan: Notes and Ideas, exh. cat. (Harrisonburg, Va.: James Madison University; York: Pa.: York College of Pennsylvania, 2010). ↩︎

For a discussion of Swiszcz’s urban iconography, see Signs and Wonders: Urban Landscapes by Carolyn Swiszcz, exh. cat. (Fargo, N.D.: Plains Art Museum, 2001). ↩︎

At the time, the Highpoint Center for Printmaking shared a street-level commercial building on Lyndale Avenue South with the Soo Visual Arts Center (Soo VAC), a nonprofit art space that also owned the building. This left no practical options for expansion. ↩︎

For more on Cucullu’s multidisciplinary practice, see Brian Sholis, Santiago Cucullu, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: Hammer Museum, 2004). ↩︎

Cole Rogers, conversation with the author, October 29, 2020. ↩︎

For more on Martin’s conceptual landscapes, see Faye Hirsch, “Cameron Martin: A Paler Shade of White,” Art in Print 2, no. 5 (January–February 2013): 27. ↩︎

For more on Rankin’s interdisciplinary practice, see Lawrence Chua and Honey Luard, Jessica Rankin: Skyfolds: 1941–2010, exh. cat. (London: White Cube, 2012). ↩︎

For more on Fischer’s multidisciplinary practice, see Anne Ellegood, Hammer Projects: Rob Fischer, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: Hammer Museum, 2009). ↩︎

For more on Helms’s explorations of social and military conflict, see Bob Nickas and William Smith, Adam Helms (Cologne, Germany: Snoeck, 2013). ↩︎

Highpoint’s board of directors convened a building committee to oversee the search for a new location. The committee was led by Thomas L. Owens, an attorney (now retired) whose practice included real estate law. ↩︎

Cole Rogers, conversation with the author, February 19, 2021. ↩︎

Thomas Owens, former Highpoint board member, conversation with the author, September 10, 2020. ↩︎

In the United States, the Great Recession refers to the sharp decline in economic activity that occurred between December 2007 and June 2009. It was the longest and deepest economic crisis since the Great Depression (1929–c. 1939). ↩︎

Zoned for commercial use, the building at 912 West Lake Street was owned by Greg Ketter, who operated DreamHaven Books and Comics at the site. ↩︎

Highpoint Center for Printmaking did not publicly disclose the price the organization paid for the Lake Street building. It did, however, disclose that the total cost of the relocation was $3.5 million, which included the building’s acquisition and expenses incurred for demolition, design, and remodeling. ↩︎

James Dayton, founder and lead architect of James Dayton Design, died in 2019, 10 years after completing the Highpoint Center for Printmaking project. ↩︎

Cole Rogers, conversation with the author, February 19, 2021. ↩︎

Vector graphics are digital graphical representations that use mathematically defined combinations of points, lines, curves, and shapes to form a picture that is both editable and infinitely scalable with no loss of image resolution. ↩︎

For a discussion of Amorales’s Liquid Archive repository of vector drawings, see Archivo Liquido – Liquid Archive: ¿por qué temer al futuro? – Why Fear the Future? exh. cat. (Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 2007). ↩︎

Cole Rogers, conversation with the author, October 28, 2020. ↩︎

For more on Piene’s drawing practice, see Barry Schwabsky, Chloe Piene: Drawings, exh. cat. (Nîmes, France: Carré d’Art Musée d’Art Contemporain, 2007). ↩︎

For more on Carter’s conceptually based practice, see Mark Rappolt, “Carter,” ArtReview, September 2009. ↩︎

“Highpoint Editions—Decade One” was on view at Mia, September 24, 2011–June 10, 2012; and Boston University School of Visual Art, Sherman Gallery, October 27–December 13, 2013. Featured artists included Kinji Akagawa, Carlos Amorales, Carter, Santiago Cucullu, Mary Esch, Rob Fischer, Adam Helms, Joel Janowitz, Cameron Martin, Julie Mehretu, Clarence Morgan, Lisa Nankivil, Todd Norsten, Chloe Piene, Jessica Rankin, David Rathman, Carolyn Swiszcz, and others. ↩︎

Cole Rogers, conversation with the author, October 28, 2020. ↩︎

For more on Willie Cole’s collaboration with Highpoint Editions, see Mason Riddle, Willie Cole: New Prints, exh. cat. (Minneapolis: Highpoint Center for Printmaking, 2012); and Jennifer L. Roberts, Willie Cole: Beauties, exh. cat. (Cambridge, Mass.: Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University, 2019). ↩︎

Riddle, Willie Cole: New Prints, p. 3. ↩︎

See Jennifer L. Roberts, Willie Cole: Beauties, exh. cat. (Cambridge, Mass.: Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University, 2019). ↩︎

For more on Spangler’s subjects and working methods, see Brian Droitcour, “Out of the Woods: In Conversation with Aaron Spangler,” Art in America, June 6, 2017, https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/interviews/out-of-the-woods-in-conversation-with-aaron-spangler-56467/. ↩︎

Aaron Spangler, conversation with the author, February 20, 2021. ↩︎

Eric Sutphin, Aaron Spangler: Luddite (Minneapolis: Highpoint Center for Printmaking, 2014), p. 11. ↩︎

For an overview of Hodges’s multidisciplinary practice, see Jeffrey Grove et al. Jim Hodges: Give More Than You Take, exh. cat. (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center; Dallas: Dallas Museum of Art, 2013). ↩︎

Cole Rogers, conversation with the author, October 28, 2020. ↩︎

Hodges’s collaboration with Highpoint Editions developed from discussions between Rogers and the curatorial staff at the Walker Art Center, which had co-organized the 2013 exhibition Jim Hodges: Give More Than You Take with the Dallas Museum of Art. ↩︎

For more on Buffalohead’s use of Indigenous themes and characters, see Anthony Ballas, “Eyes On: Julie Buffalohead and Eyes On: Shimabuku, Denver Art Museum,” Journal of Visual Art Practice 18, no. 1 (2019): 101–4. ↩︎

For more on Heikes’s multidisciplinary practice, see Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer, Jay Heikes (New York: Gregory R. Miller & Co., 2021). ↩︎

The International Fine Print Dealers Association was founded in New York in 1987. Current membership is at 146 galleries, print publishers and workshops, and private dealers. According to its mission statement, the association “fosters knowledge and stimulates discussion about collecting prints in the public sphere and the global art community.” It also sponsors annual print fairs in New York and Miami Beach and provides other marketing opportunities for its member dealers. “Mission Statement,” IFPDA, accessed May 7, 2021, https://ifpda.org/about. ↩︎

For more on Thomson’s project with Highpoint Editions, see Benjamin Levy, “Mungo Thomson: Pocket Universe,” Art in Print 6, no. 6 (March–April 2017). ↩︎

For more on Guth’s cosmological hypothesis, see Alan Guth, The Inflationary Universe: The Quest for a New Theory of Cosmic Origins (Reading, Mass.: Helix Books, 1997). ↩︎

For more on Horochowski’s vortex drawings, see Mary L. Coyne, “Alexa Horochowski: Vortex Drawings,” INREVIEW (Spring 2017), accessed April 11, 2021, http://inreview.org/vortex-drawings/. ↩︎

Akunyili Crosby’s Highpoint Editions residency was interrupted by the coronavirus pandemic and will resume in 2022. As a result, she has not yet completed any prints. ↩︎

For an overview of Carlson’s practice, see Sheila Regan, “Andrea Carlson: Anishinaabe Painter,” First American Art, no. 19 (Summer 2018): 54–59. ↩︎

For more on Gatson’s sociopolitical portraiture, see Silvi Naçi, “Rico Gatson: Power Lines, Power Minds,” Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art 44 (May 1, 2019): 144–57. ↩︎

Siddhartha Mitter, “Black Lives Shine in Rico Gatson’s New Show,” review of “Icons” at the Studio Museum Harlem, Village Voice, Jul 11, 2017, https://www.villagevoice.com/2017/07/11/black-lives-shine-in-rico-gatsons-new-show. ↩︎