III. Unlimited Editions: Four Indigenous Artists at Highpoint

- Jill Ahlberg Yohe, Associate Curator of Native American Art, Minneapolis Institute of Art

Over the course of five years, Highpoint Editions invited four Indigenous artists to its studio in Minneapolis to work through their ideas on paper, experiment with printmaking, collaborate with other printmakers, and create new work. Highpoint chose wisely, as Julie Buffalohead, Andrea Carlson, Brad Kahlhamer, and Dyani White Hawk are leaders in contemporary art whose work illuminates, in a variety of styles, content, forms, and processes, the contributions Indigenous artists have made to the field of printmaking and to art more broadly.

The resulting print editions offer glimpses into the varieties of art making by contemporary Indigenous artists and help dispel the generalizations and myths that are typically imposed upon them. All four have drawn upon their experiences, embodied histories, ideologies, and viewpoints to liberate us from our preconception of what Indigenous art is. Highpoint created a space in which each artist was given the freedom to experiment, and the results are works that allow viewers the opportunity to reflect upon our own expectations of Indigenous art.

It is only logical that, like other artists living in the United States, Buffalohead, Carlson, Kahlhamer, and White Hawk have created work informed by the geographic, political, economic, and social milieus of the places they inhabit. This essay, therefore, will focus less on the ways in which each artist is doing “Native art,” a category continually reinvented and reinforced to isolate and reify superficial notions of Native art forms and ideologies, than on how each artist created work that responds to American landscapes and the stories created within them. Like all artists, they are keen to observe, study, ponder, critique, and materialize situations, events, emotions, and perspectives that are born of the world in which they live. Each one is a truth teller, revealing the legacies and contemporary experiences often purposely obscured from mainstream history, art history, and the wider American consciousness.

Julie Buffalohead

During her residency at Highpoint, Julie Buffalohead created a series of nine prints that feature a cast of characters in the form of animals, each print telling multilayered stories and imparting important messages about personal and cultural experiences and Indigenous world views. The animals, imbued with agency, personhood, and consciousness, represent different aspects of the artist herself. The props that accompany these characters signify ideas and events from the artist’s life and also speak to broader issues of history, belonging, alienation, and nationhood. Buffalohead’s animals are captivating; they pull the viewer into her worlds, compelling the viewer to bring his or her own perspective into the stories they tell and the feelings they express. These narratives speak to tough issues, including violence, colonization, and genocide, but also to compassion, love, and grace.

Throughout her career, Buffalohead has created a visual language from personal experience. At the time of her residency at Highpoint, Buffalohead was in the midst of juggling the care of her young daughter with her continuing art practice. Motherhood prompted her to reflect on her own childhood in a Minneapolis suburb, where, as a Native person, she faced oppression, alienation, and bullying. And there are further tensions in her living far from her Ponca homeland. The Ponca people have been forcibly removed from their homelands over and over again, interned in reservations by the United States government. Buffalohead’s work also includes references to Indigenous issues more broadly, including appropriation, exclusion, and the erasure of Indigenous peoples from the American consciousness. Yet her artwork also reveals the ongoing presence and vitality of Native life and the personal and cultural meaning of being an Indigenous and Ponca woman in contemporary America.

Buffalohead’s art makes the connection between agency and chaos. She is intent on presenting disruption and finding meaning in chaos. The rabbits and coyotes that feature prominently in Buffalohead’s work often play the part of trickster in Native storytelling; they create ambiguity and sow confusion yet show the range and contradictions of humanity, not as victims but as protagonists of the stories, with their own power to create universal and specific experiences in response to the effects of colonization on the landscape and individuals.

Figure 3.1

Figure 3.1In Revisionist History Lesson (2014) (fig. 3.1), a coyote lies on her back, with head, paws, and tail extending upward. Attached to her paws are lines that hold props, flat cutout shapes in the form of North America, a rabbit, a vessel shaped in the image of one of Columbus’s ships, and a turtle holding an arrow. Buffalohead’s work is never meant to be reduced to a single interpretation; instead, her characters guide the viewer toward inference. The silhouettes of North America and the sailing vessel may be interpreted as embodiments of Western colonialism, which held that the world was a place to be mapped, objectified, and owned. In contrast, the other figures—the rabbit and turtle—might suggest Indigenous perspectives on land and place, the stewardship of Turtle Island (America), and the role of animals in Ponca creation stories that guide individuals in the appropriate ways of being and acting in the world. At the center is the coyote, connected by lines to these other elements, close examiner of and witness to the props, the one who orchestrates the perception point from which the viewer can observe and reflect. While the props are dark and flat, mere objects, the coyote is filled with subjectivity (self-awareness, volition, agency). She is rendered with exactness, tenderness, and texture, each detail of her physicality carefully shaded with precision and care.

Figure 3.2

Figure 3.2 Figure 3.3

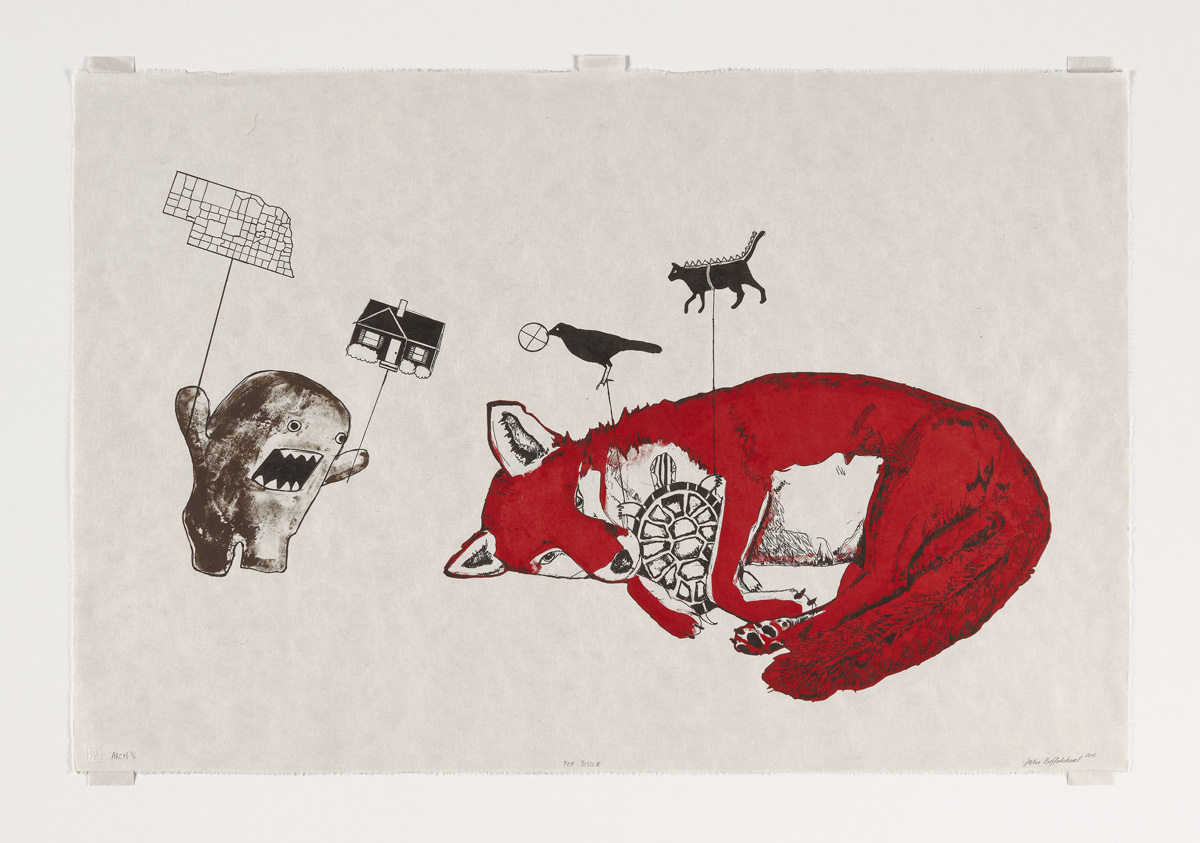

Figure 3.3Like Revisionist History Lesson, Buffalohead’s other Highpoint works serve as commentaries on colonization and the appropriation of Indigenous land by settlers. In Fox Tussle (fig. 3.2), a red fox clutches and protects a turtle while a large alien figure screams. The figure is holding a map of Nebraska and a quintessentially suburban home, props that identify American settlement and land seizures.

These commentaries on U.S. history and dogma also appear in more domestic settings, revealing the impact of colonization on everyday life. Buffalohead questions traditional gender roles, feminine beauty ideals, and mythologies of motherhood. In The Vanished (2015) (fig. 3.3), she mines rich social commentary in mundane objects like lawn chairs and items associated with children and play, things that, as a mother of a young daughter at the time, surrounded her; the coyote-woman dressed in 1950s-style attire epitomizes what the artist calls the “achievements of domesticity.”1

Figure 3.4

Figure 3.4 Figure 3.5

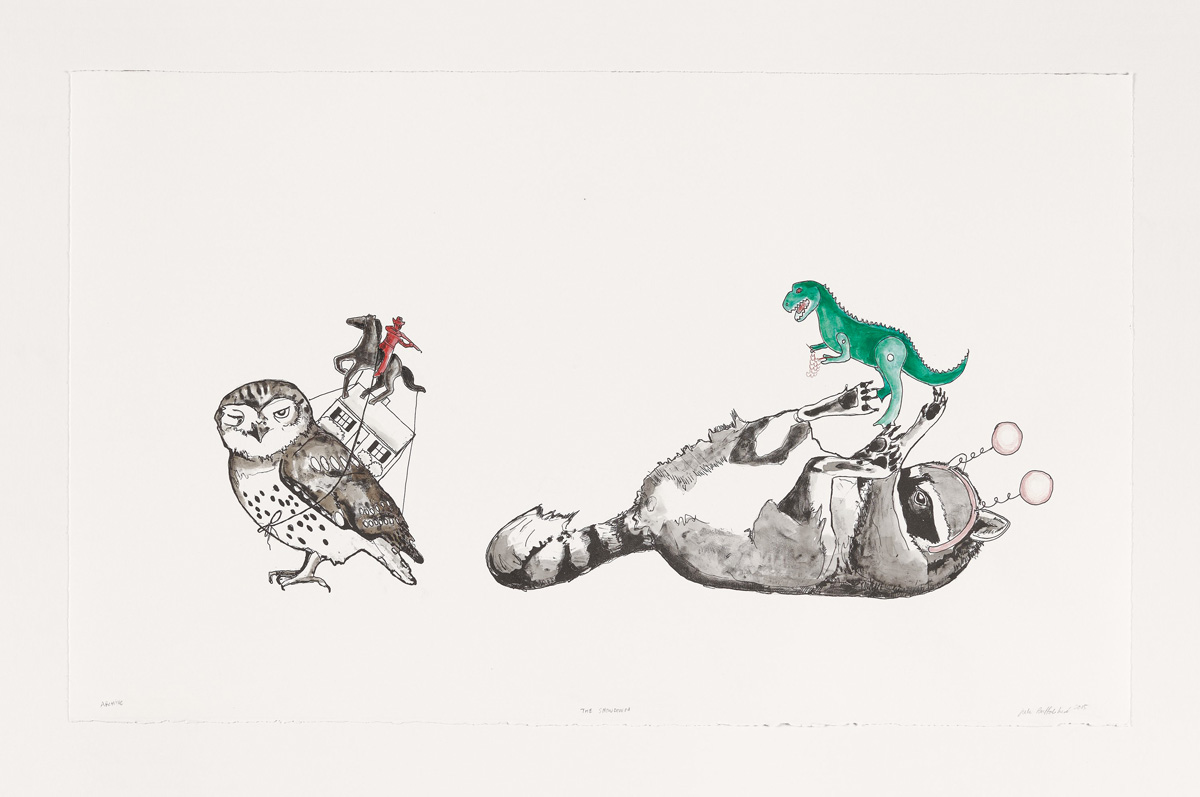

Figure 3.5Houses are placed on the backs of owls (figs. 3.4 and 3.5); dolls’ clothing is hung on a clothesline strung between deer antlers (fig. 3.6). These disparate, ordinary objects, juxtaposed with her charismatic animals, represent the intertwining of personal history with a broader American history.

Figure 3.6

Figure 3.6Brad Kahlhamer

Brad Kahlhamer’s career as a practicing artist spans four decades in which he has found inspiration from a variety of what might seem like unlikely sources—his experience as the artistic director and graphic artist for Topps chewing gum, the solitude and open expanse of the Southwest desert, historical Plains ledger art (Bear’s Heart ; William Cohoe ; Koba ; Attributed to Ohet-toint ), the raging 1980s punk rock scene on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, and his collections and classification of all sorts of things: katsinas, animal skulls, cacti, just to name a few. Kahlhamer’s compositions are filled with highly personalized biographical information and refreshing honesty and reflect the work of an artist who thinks deeply about notions of identity and belonging and issues of representation. His works, with their visual riffs on celebrated iconography in Western and Indigenous art, are disruptive critiques. In them, it is hard not to see Kahlhamer’s continuous wrestling with aspects of himself, particularly his unresolved ancestry and unknown tribal affiliation. Kahlhamer’s own biography is in part a product of an era of tragic federal policy in the mid- to late twentieth century that removed infants and children from Indigenous families and placed them into white households. As a result of this policy, it is nearly impossible for adoptees to reconnect with their birth parents and community.

Yet within Kahlhamer’s work, this loss of ancestral legacy is not revealed in terms of bitterness or victimhood but rather as a source of strength and a personal odyssey; it is the driving impulse for his constant stream of activity. The absence of his tribal identity has created a space for reimagining his identities and the manner in which he creates art, something he describes as the work of “a nation of one.”2

Like all artists, Kahlhamer brings aspects of his multiple identities and experiences to his work, which he uses to make sense of his identity—both the invisible ties to his Indigenous ancestry and the identifiable and self-created aspects of himself—as an illustrator and graphic designer, as a lifelong musician, and as a resident of New York City. And Kahlhamer’s long association with New York’s Bowery neighborhood and its punk scene is evident as well: rebellion, individuality, and ideals of personal expression are central to his work. Kahlhamer chooses freedom and the disruption of expectations imposed on Indigenous artists from the outside.

Figure 3.7

Figure 3.7 Figure 3.8

Figure 3.8 Figure 3.9

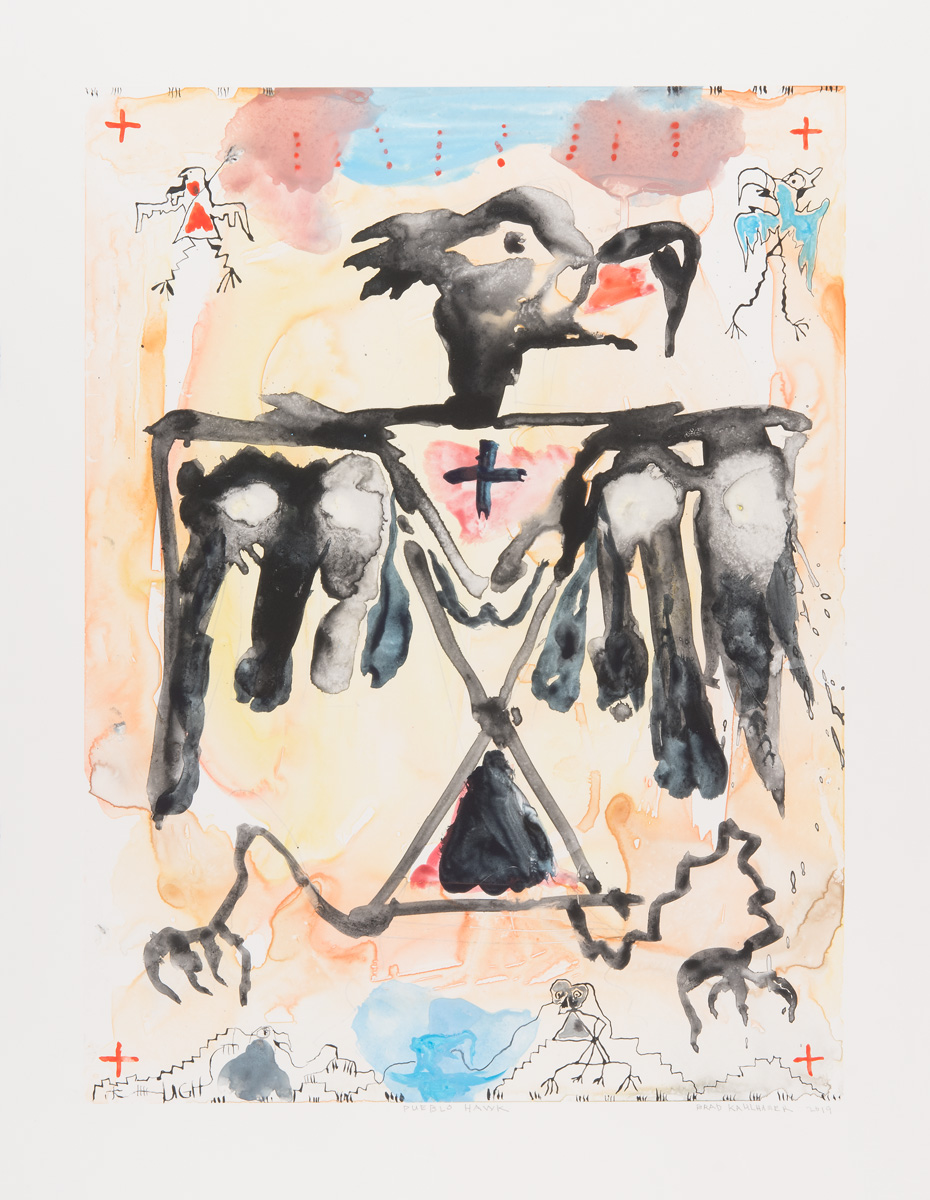

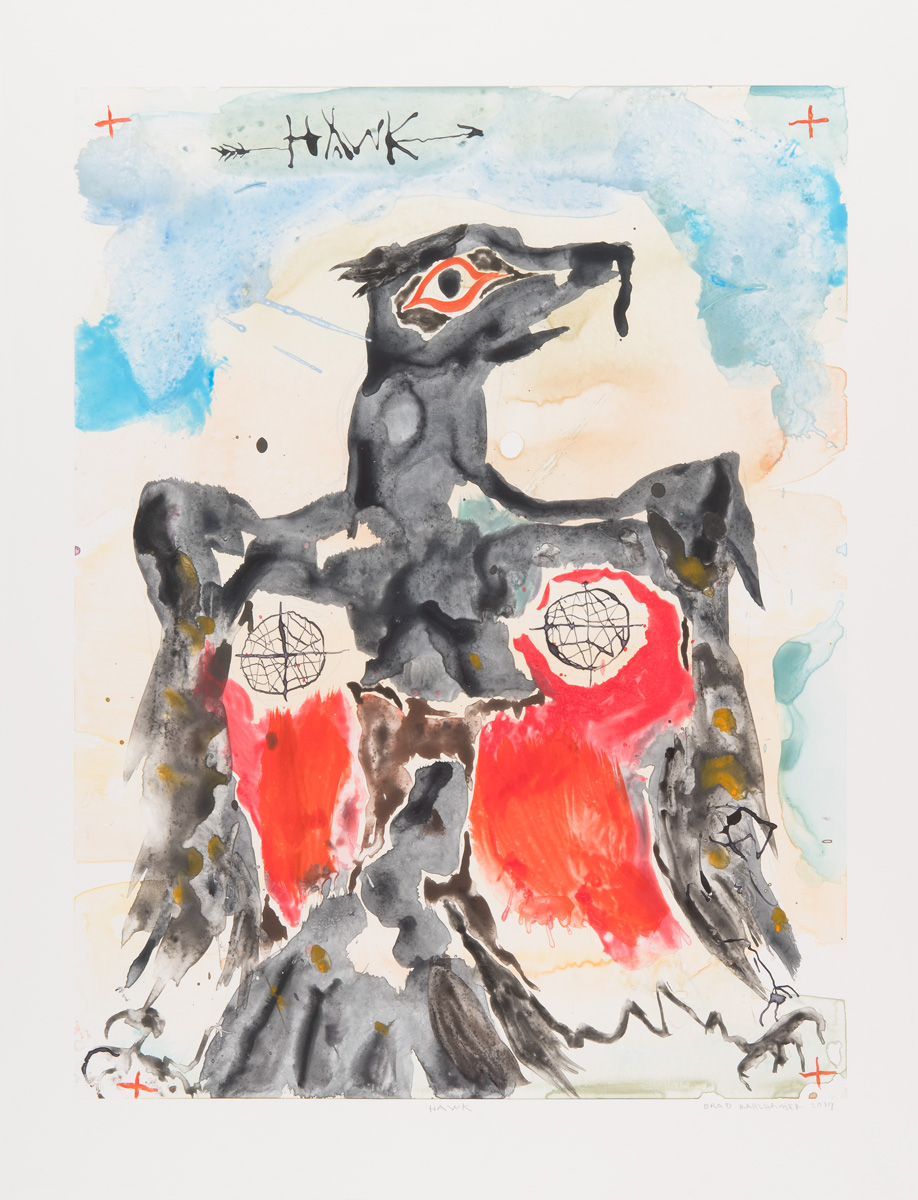

Figure 3.9Raptors, particularly hawks and eagles, have followed Kahlhamer throughout his life, whether soaring high above the buildings of New York City or initiating close encounters in the desert lands near his second home in Mesa, Arizona. Hawks and eagles are also present in many of Kahlhamer’s paintings and works on paper and are the primary subjects of the monotypes he created at Highpoint during his residency (figs. 3.7, 3.8, 3.9). Raptors serve, in part, as what he calls “reductions of animism,”3 found in the iconography of historical Indigenous art; thunderbirds, eagles, and hawks have played a prominent role in North American art for millennia, and their likenesses are found in petroglyphs and in pottery, textiles, and many other belongings meant for personal and community use.

At Highpoint, Kahlhamer selected watercolor as the medium in which to convey these raptors, finding, he says, that it aligns with his own artistic practice of “repetition, replication, and continuation of form and theme.”4 What results is a sense of controlled spontaneity and immediacy, a body of work that is succinct yet multivalent. Within the work there is both rebelliousness and controlled movement. Soft gestures and distortion exist side by side.

Kahlhamer describes his residency at Highpoint as magical, a place and time of unrestricted freedom to create on his own terms, with talented collaborators to assist him. The series of watercolors he made there illuminates the spontaneity and repetition of Kahlhamer’s artistic style. Broad strokes, energetic lines, and soft backgrounds are sliced with black, piercing claws. In most of his monoprints, a thunderbird, hawk, or eagle appears, which Kahlhamer uses as an ironic commentary on iconic symbols often used to define Native art. Here, the artist employs it as a self-conscious acknowledgment of its problematic associations. Dripping ink signifies fluidity—both in his artistic approach and in the many meanings associated with hawks and eagles within different Indigenous communities. Kahlhamer also inserted himself into many of the works and included sets of four—crosses or additional figures—symbolizing the importance of four in Indigenous communities, but the referents remain unspecific.

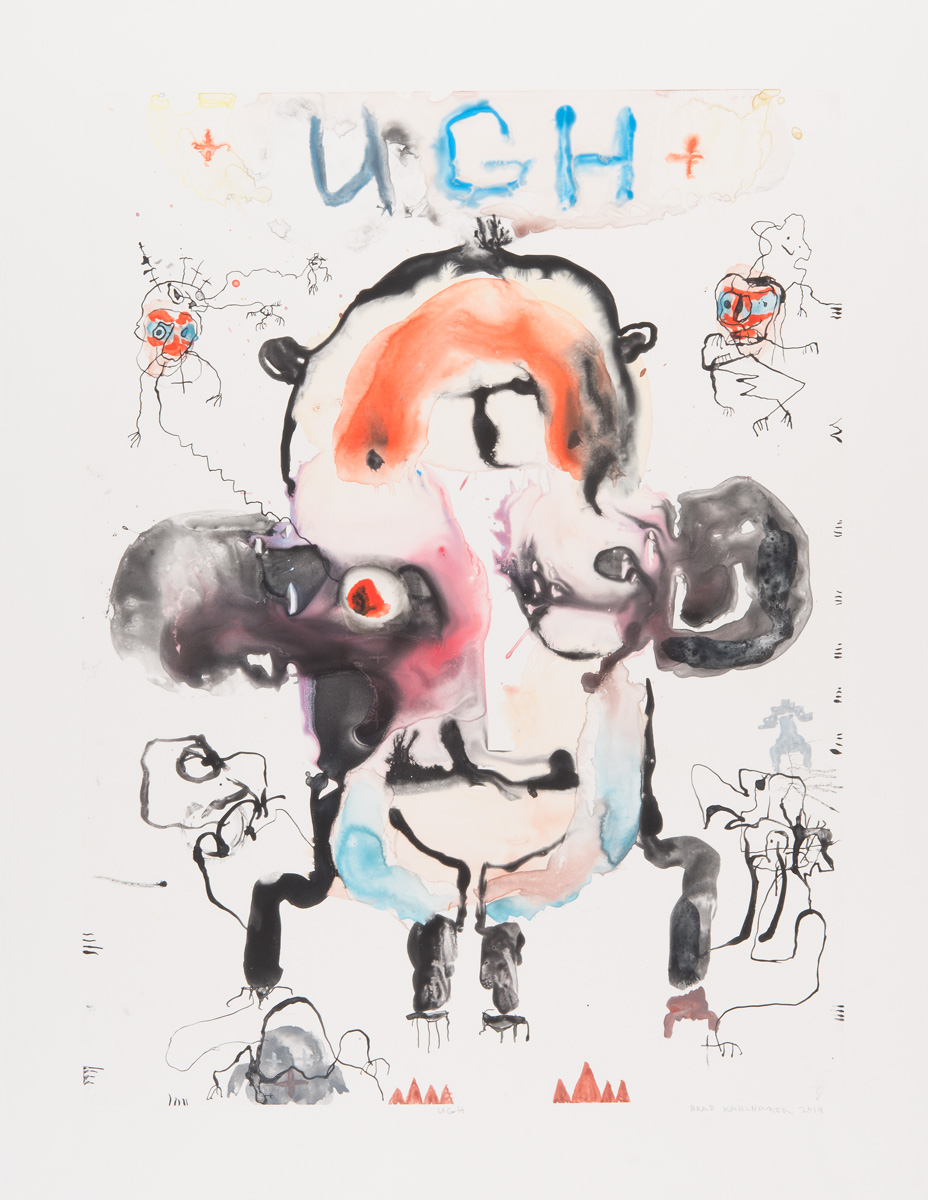

Figure 3.10

Figure 3.10In Ugh (2019) (fig. 3.10), a humanlike blob appears at the center of the print, likely representing Kahlhamer himself. At the top he wrote “UGH,” a recognition of his own complex identities. Aspects of living in many worlds—Native and non-Native, Mesa, Arizona, and New York City—are also depicted; the environments that have shaped his experiences of life are distorted and chaotic, at once certain and uncertain.

Andrea Carlson

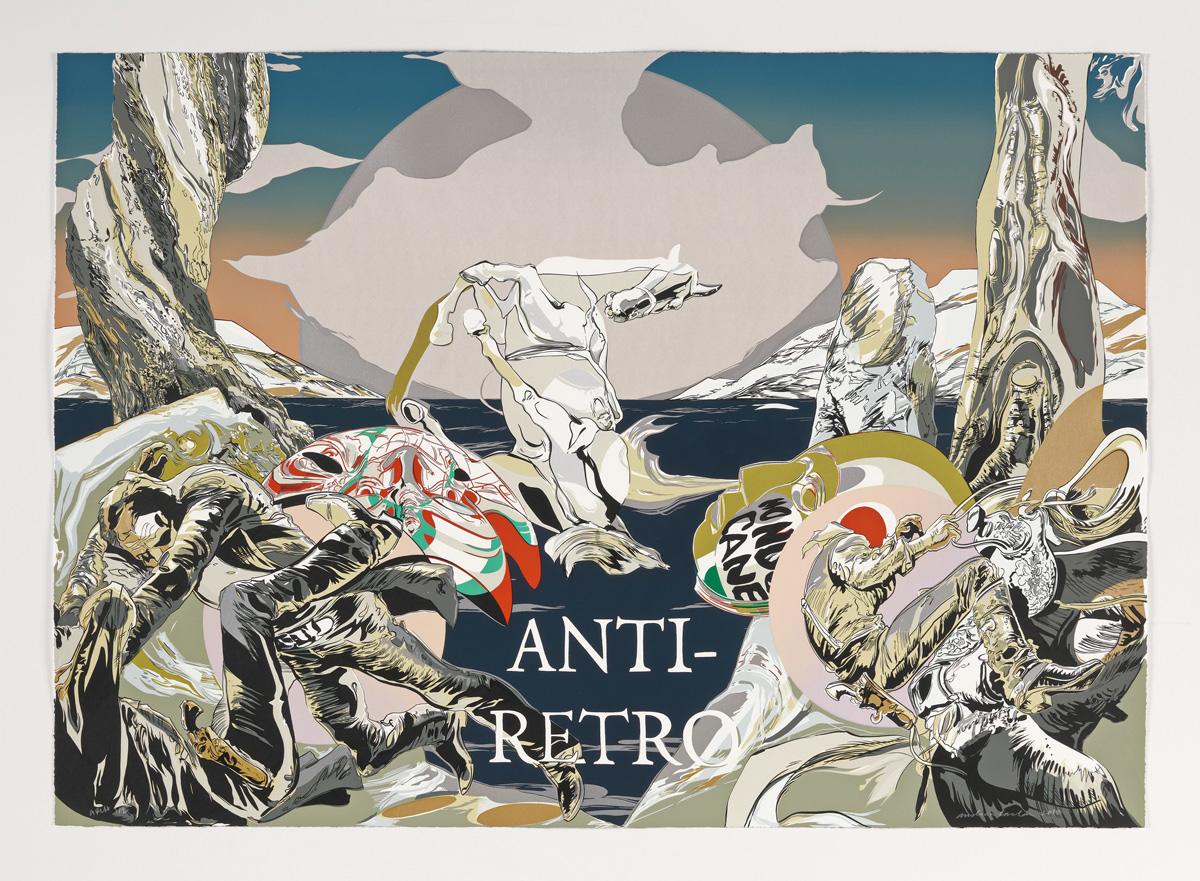

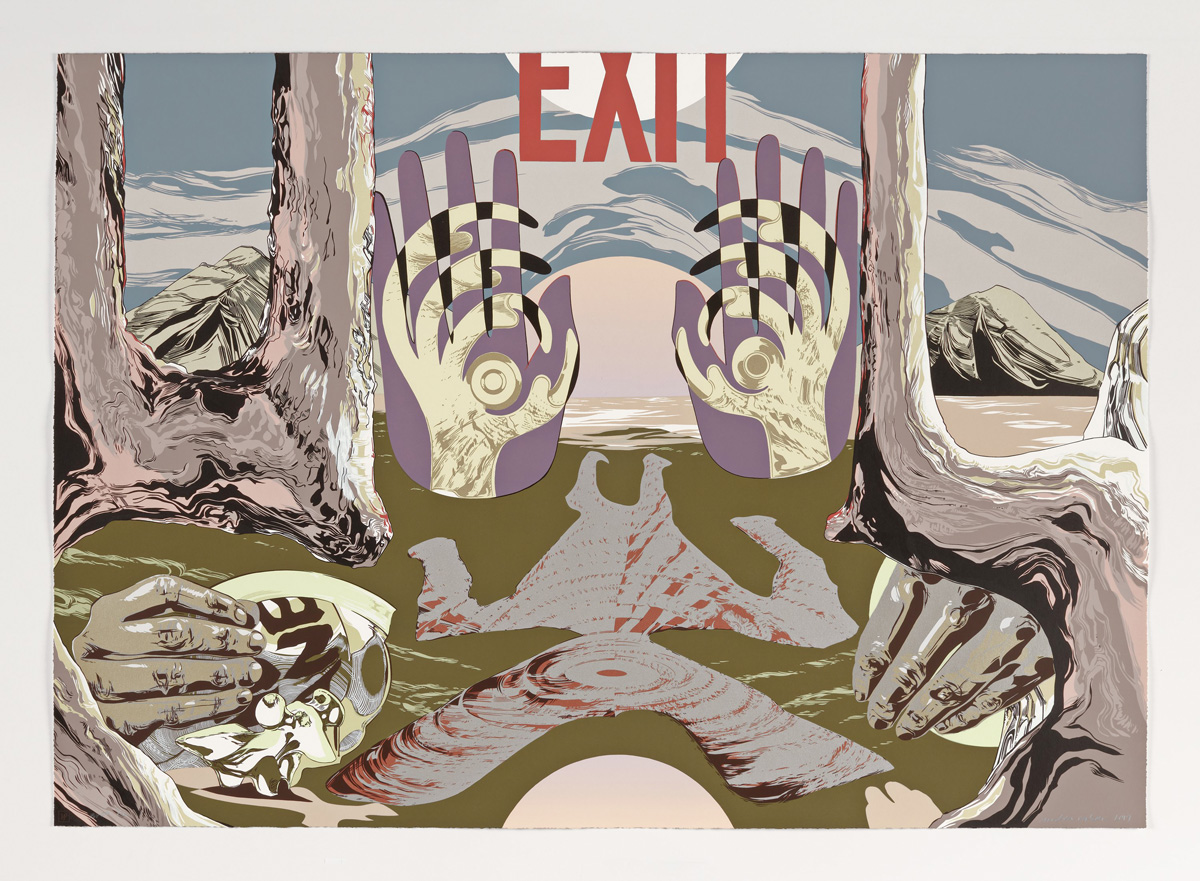

Andrea Carlson is known for her multilayered landscapes or shore scapes that reference various places, ideologies, objects, events, visual narratives about erasure, representation, histories, futures, and what she calls “the entanglements of presence.”5 It is staggering to learn that Carlson’s collaboration with Highpoint was one of her first deep explorations in printmaking, as her work, with its crisp lines, polished surfaces, multiple layers of paint, and exacting draftsmanship, is characteristic of master printmakers. The two screenprints, Anti-Retro and Exit (figs. 3.11 and 3.12), contain more than eighteen layers of color, a massive project for a printmaking initiate.

Figure 3.11

Figure 3.11 Figure 3.12

Figure 3.12Carlson presents seemingly infinite layers of meaning, vantage points, perspectives, and signifiers drawn from art history, critical theory, history, Indigenous philosophies and practice, and her ideas of the future. In her prints Carlson is an anti-cartographer of colonial social landscapes, rendering the events and truths that remain hidden by the mythologies of colonization. She brings into focus the contradictions of representation that have been left untold, exposing acts of violence against the land, people, and beings, and Indigenous responses and extraordinary resiliency in spite of these acts. In so doing, Carlson generously yet honestly offers the viewer opportunities to question the assumptions they hold, reflect on the histories they believe, and arrive at new ways of understanding, relating, and acting in the world.

Each of Carlson’s works at Highpoint is like a portal into an alternative universe, where the legacies of colonization are reversed, and the Indigenous presence is dominant. In her first print, Anti-Retro (fig. 3.11), Carlson depicted water in the deepest of green as the surface of the narrative, in which falling and frozen figures, candy-cane-color masks, and gnarled trees collide. In the background, Carlson incorporates her signature horizon line and creates a vast orange and green sky, with monumental rock formations cutting the surface between earth and sky. Drawing upon critical theory by Indigenous and non-Indigenous scholars that rejects notions of the past, Carlson inserts cowboys in uncontrolled motion, clumsily falling into the landscape. Rather than the stoic, invulnerable heroes of American lore, these cowboys are unstable figures, collapsing under the world around them. Their multicolor masks refer to “shockumentary” movies like Mondo Cane (1962) that reify imaginary and damaging portrayals of the Indigenous “other.” At the center, a tumbling horse remains frozen in time but not in control of a human rider.

Place and time are also key themes of Anti-Retro. A tree appears on each side of the print, one from Joseph Beuys’s 7000 Oaks project , which asserts relationships between built environments, ephemerality, and nature, and the other the Little Spirit Cedar Tree of Carlson’s own Grand Portage community. Anti-Retro, a term first used by Michel Foucault to reconsider history as a construct, here applies to Carlson’s interest in confronting American mythologies of Native peoples in history. In this way, Carlson presents an alternative response to the notion of a static history and, in so doing, reveals the potentialities of the future. In this sense, Carlson is asserting the idea of Indigenous futurism. Her art acknowledges that Indigenous people have always had philosophical systems that point to both the construction of history and the future.

Indigenous futurism is just one premise on the nature of Indigenous reality (ontology) among many Indigenous theories of life. In Exit (fig. 3.12), her second Highpoint screenprint, Carlson lays bare the realities of the past—of cultural loss, change, destruction, removal, and erasure. Exit serves as an homage to the ancient Indigenous social and aesthetic systems that endure. While the red Exit sign represents the fear of loss, Carlson includes the forms of two iconic works of ancient art—the mica hand/talon

of the Mississippian peoples (in yellow and purple) and Mound Man, an earthen figure in rural Wisconsin—as repositories of the past and testaments to the creative genius of their makers. The subtle pastel tones, marbled light skies, and aged and burled trees create a sense of enduring time and place, with civilizations ever present. At the center she has placed an effigy figure, Mound Man. This mound and thousands like it across the Upper Midwest have encountered different fates, some cut into two, some destroyed by settlers, and some purposely hidden from view. Yet their presence, like Indigenous people, has endured from time immemorial and is never ending.

Dyani White Hawk

As a young art student, it didn’t take Dyani White Hawk long to realize why the work of American Abstract Expressionists and Minimalists appealed to her. White Hawk recognized that abstraction was a fundamental Lakota—indeed, Native—aesthetic, one she’d been immersed in from a young age. Yet there were clear distinctions to be made between abstraction found in mainstream American art and in Lakota art, because the two cultures have radically different ways of seeing and being in the world.

For instance, Abstract Expressionism, developed and based in post–World War II New York City, emerged because individual artists were attempting to liberate themselves from the conventions and limitations of the past. They saw painting not as a way to depict the human figure and the world around them but as an immediate, spontaneous, and gestural form of self-expression, a way to seek out elemental and universal truths. In contrast, White Hawk was aware of Lakota abstraction, a sophisticated and long-standing art form that emphasizes and expresses Lakota values of creation, respect, relationships, responsibility, and care. Through her own work in abstraction, informed by both traditions, White Hawk is able to expand and deepen the history of abstraction in American art, thereby broadening the art-historical record to include Indigenous artists, Indigenous aesthetic canons, and Indigenous systems of thought that have existed for centuries, if not millennia.

Figure 3.13

Figure 3.13 Figure 3.14

Figure 3.14 Figure 3.15

Figure 3.15 Figure 3.16

Figure 3.16In her Highpoint suite, “Takes Care of Them,” White Hawk created a series of four prints that, on the surface, depict four Northern Plains–style dentalium-shell dresses . Each dress exhibits the fundamental aesthetics of dentalium dresses, including a field of saturated background color (green, red, gold, and blue, respectively) representing the wool bodice of the dress, a dentalium-shell yoke, and additional embellishments at the hem. Within these works White Hawk incorporated additional meanings that lie beneath the surface. The of four prints embodies core elements associated with women in Lakota society that speak to an ethos of caring, relationships, kinship, and the practice of being a good relative. The conceptual basis of the work is communicated through the series title “Takes Care of Them”; the prints’ individual titles, Wówahokuŋkiya | Lead (fig. 3.13), Wókaǧe | Create (fig. 3.14), Nakíčižiŋ | Protect (fig. 3.15), and Wačháŋtognaka | Nurture (fig. 3.16); and the suite’s expression of the value of the collective and the individual. With this series, White Hawk elaborates upon abstract thought rooted within Lakota aesthetic canons and practices, informed by Lakota ontologies and epistemologies.

White Hawk creates works of art that reveal the relationships between the dresses’ makers, the materiality of the dresses themselves, and the objects that adorn each dress. Lakota women do not create these dresses as mere expressions of self, but rather as expressions of relationships. The act of creating the dress is essential, yet the dress itself is not the final product, like a work of art to be hung on a wall and admired from a distance. Often these dresses are made for friends and loved ones. Or, multiple family members may pitch in to create a dress for a new season of dance, a life transition, or an accomplishment. To create a dress for another is to adorn them with care, love, dedication, protection, strength, and beauty, to make a work of art that reflects and makes material an ethos and an act of love. Even when creating a dress for herself, a Lakota woman is wrapped in the traditions of her people, partaking in long-held artistic practices and participating in cultural doings that support the cultural continuity of her people.

Each of the four prints exhibits the intentional, precise craftsmanship found in the dresses themselves, and White Hawk reveals her understanding of the materiality of the pieces that make up the dresses and the formal elements of design used to create them. Wówahokuŋkiya | Lead, Wókaǧe | Create, Nakíčižiŋ | Protect, and Wačháŋtognaka | Nurture depict the array of materials—shells, silk, ribbon, wool, sequins, metal disks, coins—that are used in a variety of unique combinations in each dress. Dentalium shells are carefully rendered in rows, creating a centralized half-circle design representing the yoke on each bodice. White Hawk says, “The dresses, each adorned in their own unique format, are meant to represent both long-standing practices of the making of and traditional aesthetics of dentalium dresses, as well as the individual creativity and unique personalities of each wearer.”6 They also reveal the ingenuity and sophisticated nature of Lakota artistic practices, particularly in the incorporation of materials from many cultures and lands, such as European trade cloth wool, Northwest Coast dentalium, conch, and cowry shells, French ribbon, and U.S. currency.

The works of these four artists reveal that Indigenous art is not historical and unchanging but a constantly shifting, continuously emerging field, one in which artists draw upon a variety of sources and inspiration. Furthermore, they offer viewers an opportunity to think more deeply about how we view Indigenous art and the history of art more generally. It is my hope that this essay has done the exact opposite of what I said in my introduction. This essay is, in fact, an attempt to contribute to what Native art is, by focusing on the work of four Indigenous artists in one particular time and place. This is Native art—works arising from individual artistic expression and informed by enduring aesthetic canons. This is what Indigenous art is and has always been. These artists locate themselves to varying degrees within the landscape of American art more generally. Highpoint Editions provided them with opportunities to recognize the fullness of their art and to expand the field, not by placing conditions or expectations upon them, but by offering them opportunities to explore whatever they desired to create.

Notes

| words